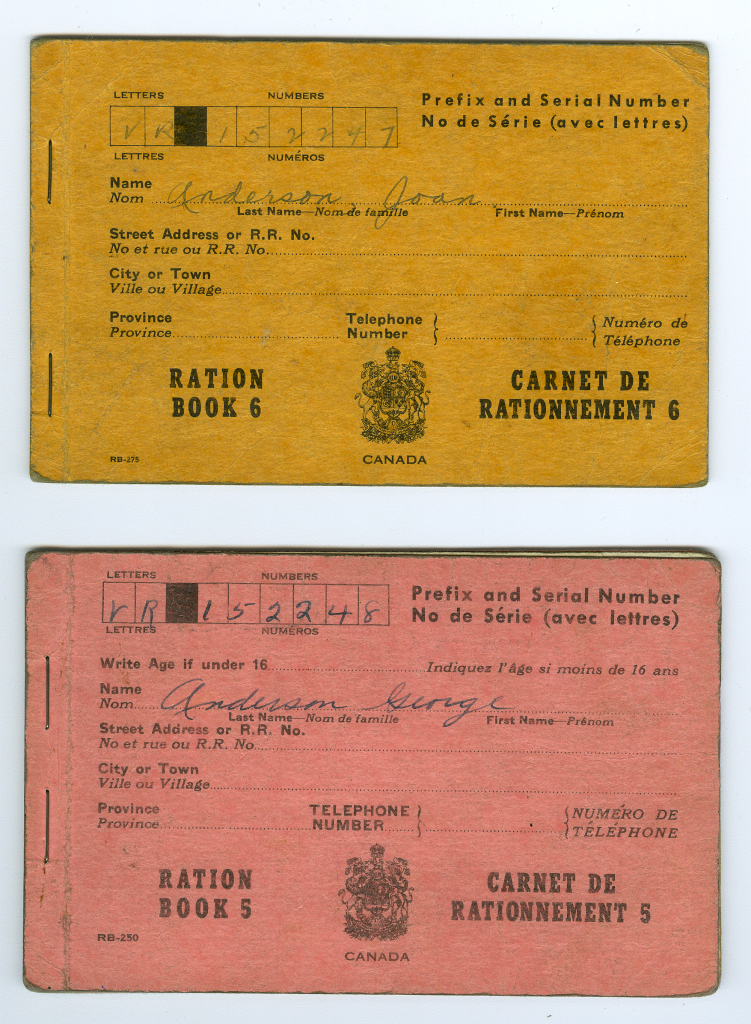

In 1942, the nation of Canada instated new laws back at home in efforts of supporting the soldiers they’d sent overseas. In order to ensure that the allies stationed in Europe would have enough rations, Canada began rationing the food consumed in its own territory through the distribution of tokens and tickets.

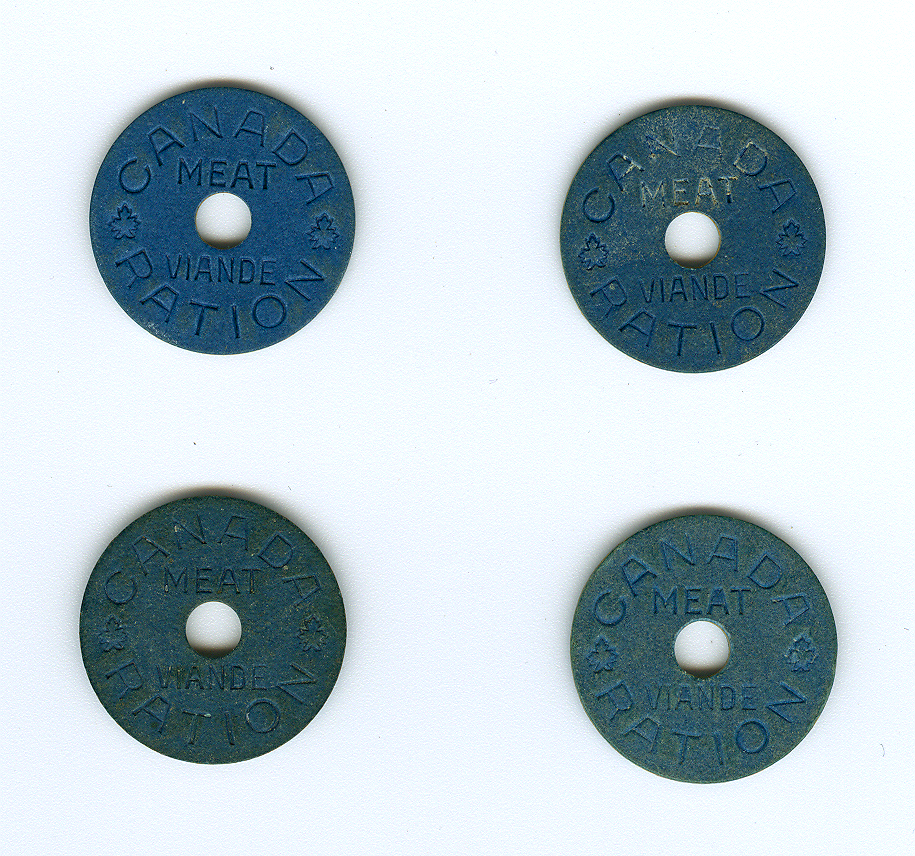

Pictured here are real ration tokens from the 1940s. These tickets would have to be ripped from their booklet in the presence of a grocer in order to be accepted, and were used in place of currency to pay for the weekly groceries. Inside the booklet, the ration tickets come in multiple colours, with one colour to represent each of Canada’s limited resources, such as the very-limited tea, coffee, and butter. While one ration of meat counted for 2 pounds per person per week, not all families bought all their weeks meat in one shopping trip. The blue tokens pictured would be used as “change” of sorts, where families who only bought a portion of their meat could come back later in the week to buy their remaining rations. This ensured that less meat went to waste, since the meat that was purchased later in the week was sure to be fresh, as opposed to the meat that had been in storage for a couple of days.

Canada did not experience any serious shortages of important foods during the rationing period, though the rations to kitchen staples meant Canadians had to get creative when preparing their meals. Limits to meat portions increased consumption of beans, eggs, and (surprisingly), lobster as alternate protein sources. Lobster, in fact, was being promoted by the Canadian government as a “patriarchal meal” for how its consumption supported the struggling fishing market after many fishermen had gone away to war.

While the transferring or swapping of ration booklets was forbidden and punishable by anything from fines to jail time, coupon exchanging was an incredibly common practice between neighbours. For example, people who didn’t drink couldn’t make use of their alcohol rations, and so traded away their tickets in exchange for extra rations of coffee or tea. Some neighbours would even give away the coupons they didn’t need for nothing in return; if your household didn’t use much sugar but your friends down the road often did, it wasn’t unheard of to hand them your unused sugar coupons so they wouldn’t go to waste.

Despite the stern warnings printed on the inner cover of the booklets that unlawful exchange or gifting of ration coupons would under no circumstances be tolerated, the community did so anyways. While the circumstances of the war were taking their toll, neighbours were coming together in cooperation to share what they had with one another and ensure everyone had what they needed to feed their family. Though these ration coupons seem terribly bleak upon first glance, their history reminds us of the innate human instinct to take care of one another in difficult times.

This blog post was researched and written by Camryn Page, SFU.