Patent medicines, which were generally neither patented nor actual medicine, were common in late nineteenth century medicine cabinets. These compounds, tinctures, liniments, and “herbal remedies” were peddled as medicines by charismatic salesmen and clever advertisements, especially in small communities that lacked doctors, such as early Maple Ridge. These medicines often advertised seemingly healthy herbs and vegetables that they supposedly contained, although there were no regulations governing accurate advertisements and many actually primarily contained alcohol, opium, cocaine, and laxatives. Patent medicines advertising as cold medicines often contained cocaine, giving the illusion that the cold was gone and your energy was back. Those advertising as pain and ailment relief usually contained alcohol, opium, heroin or a combination of all of them which would numb the pain but cause severe addiction and further health problems. Finally, almost all patent medicines contained some kind of laxative as it was the easiest to manufacture and would absolutely have an effect on the body, giving the impression that it was at least doing something.

This is a selection of the patent medicines in our collection.

This blog was researched and written by Madelyn Huston, UBC.

Burdock Blood Bitters

Burdock Blood Bitters was a Canadian invention first produced by the T. Milburn Company, an Ontario-based patent medicine company, in 1877. The product was advertised as a blood purifier that cured a wide variety of ailments, including “biliousness [bad digestion], constipation, kidney and liver complaint, impure blood, dyspepsia [indigestion], headache, bad circulation, obstinate humours, scrofula [a disease of the lymph nodes caused by an infection, often tuberculosis], old sores, general and nervous debility, female complaints, and all irregularities of the system caused by bad blood or disordered action of the stomach, bowels, liver, and kidneys” according to one advertisements (link to ad in U of T collection?). These various claims were reinforced by testimonials, supposedly from pleased customers, in the Burdock Blood Bitters Almanac published yearly by the T. Milburn Company (outside link).

While this particular bottle does not include a list of ingredients, the National Museum of American History has a bottle of Burdock Blood Bitters from the New York-based Foster-Millburn Company, which lists “Burdock Root, Yellow Dock, Dandelion, Senna, Cascara Bark, Golden Seal, and other well-known roots, herbs, and barks. It contains no alcohol or harmful ingredients of any sort.” A lot of these ingredients have historically been used in a medicinal setting. For example, the namesake ingredient, burdock root, has traditionally been used as a diuretic and a digestive aid. Interestingly, two of the ingredients, senna and cascara bark, are traditional laxatives, and yellow dock may also function as a laxative for some people. So, while Burdock Blood Bitters was unlikely to cure all of the advertised ailments, it may very well have been helpful at least for constipation.

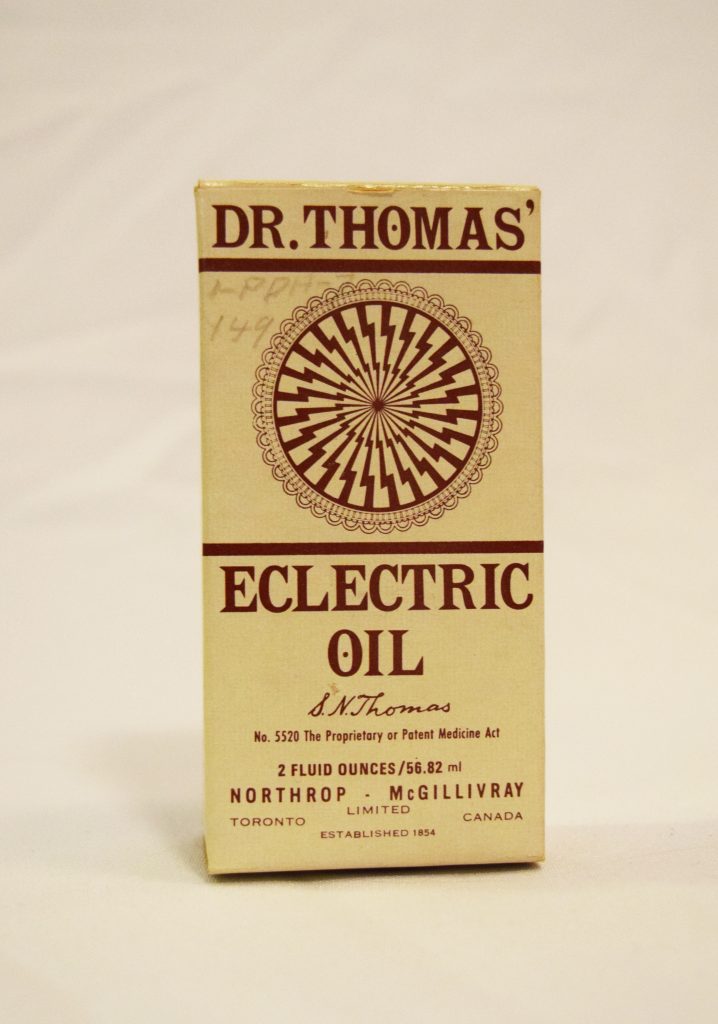

“Dr.” Thomas Eclectric Oil

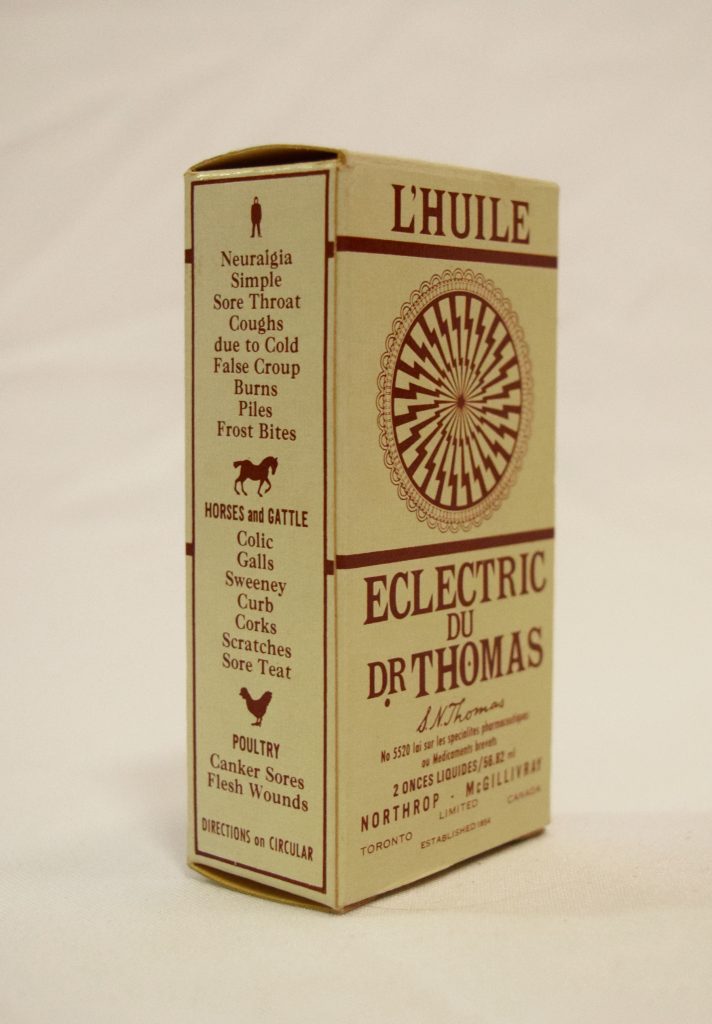

Many patent medicines were advertised as being the invention of a clever doctor that was simply being distributed by a larger company. In some cases, that was likely true. An individual (though not necessarily a doctor) would develop a medicine and then sell the rights to manufacture, advertise, and sell the product to a large company. In other cases, the individual was probably invented. Dr. Thomas’ Eclectric Oil is most likely an example of the former, as records from the late 1860’s confirm a Samuel N. Thomas, listed as an electric physician, living in New York, which matches the advertised Dr. S.N. Thomas of New York to whom the product was attributed. The title “electric physician” likely refers to the field of electro-biology, which focused on the potential of electric and magnetic forces in healing. The term “Eclectric Oil,” under which this product was distributed in Canada by Northrop & Lyman (it was called “Canadian Healing Oil” in other parts of the world) drew on people’s beliefs around these electric forces. This presented the product as a form of advanced technology and developments in science in order to lure in potential customers. This is on the opposite end of the spectrum from many other patent medicines, which emphasized herbs and vegetables to advertise traditional, reliable medicinal properties.

The Eclectric Oil was marketed as a cure for essentially anything and everything. For humans, the box claims that it can cure neuralgia (nerve pain), simple sore throat, coughs due to cold, false croup, burns, piles, frost bites, and many more ailments. Not only did this Eclectric Oil supposedly heal humans, the product was also advertised as being useful for farm animals, including horses, cattle, and poultry. This was probably added to appeal to families in predominantly farming towns who relied on livestock, in hopes that they would frequently purchase the product to handle all human and animal ailments they faced.

In reality, Dr. Thomas’ Eclectric Oil was primarily made of basic oils, including fish oil and oil of thyme, and camphor, not electricity or magnets, and it cured nothing.

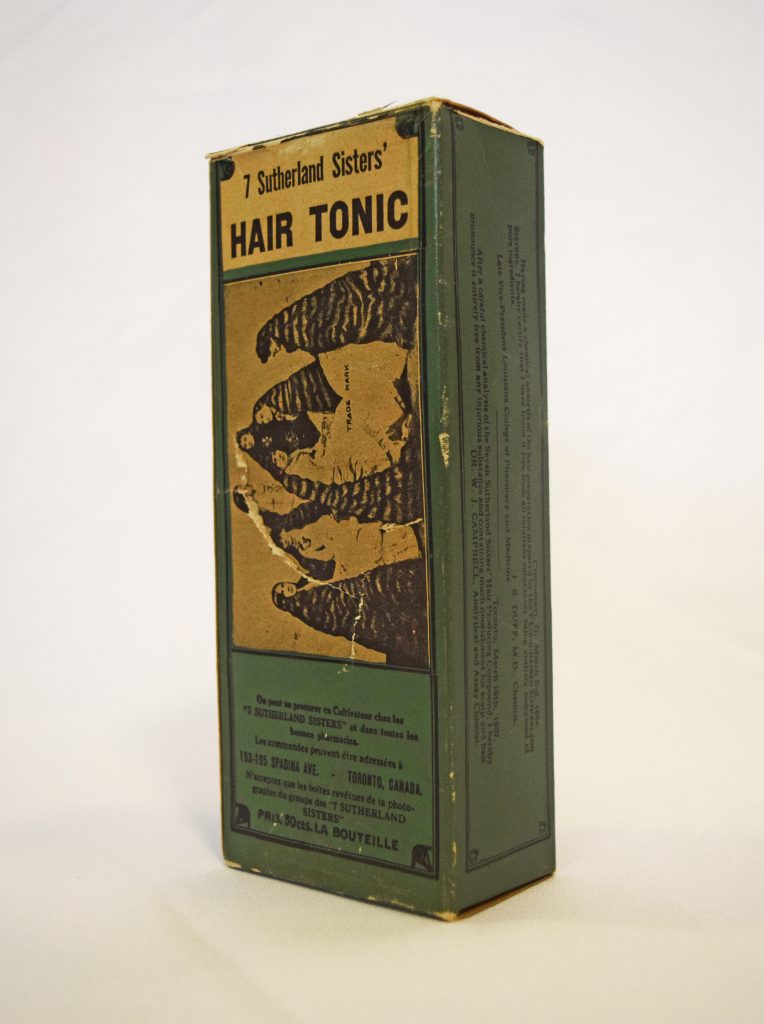

7 Sutherland Sisters Hair Tonic

The Seven Sutherland Sisters hair tonic is only one part of the Seven Sutherland Sisters brand. The namesake seven sisters, Sarah, Victoria, Isabella, Grace, Naomi, Dora, and Mary, had a popular singing act in the late 19th century. However, their fame did not come from their voices as much as from their extraordinarily long hair, advertised at times as seven feet of hair each (although in reality only Victoria likely had a full seven feet of hair, and some of them had as little as three feet). Their hair was such a curiosity that they actually partnered with Barnum & Bailey’s circus as a sideshow act. While this was quite successful, the family decided to expand their brand by selling a hair tonic that purportedly had given the sisters their luxurious hair.

This hair tonic was patented in 1883, and it was originally accompanied in many advertisements by an endorsement from a chemist, who stated that it was “free from all injurious substances, being entirely composed of Vegetable Preparations.” This endorsement also called it “the best preparation for the Hair ever made.” (http://www.sideshowworld.com/13-TGOD/2010/tgod7sutherlands.html) This tonic was certainly not entirely composed of vegetables. In fact, it was primarily made of witch hazel and bay rum, with some salt, magnesia, and hydrochloric acid (to get rid of the yellowish colour produced by the reaction of the witch hazel, bay rum, and magnesia). Witch hazel is a plant, but it is a flower, not a typical vegetable, and there is no evidence that it has any hair-growing properties. It is obvious that the family was more concerned about selling their product than about the truth.

The Seven Sutherland Sisters brand expanded over time to include hair brushes, a scalp cleanser, and “colorators.” While the brand was quite successful for several decades, it eventually declined in popularity, perhaps due to the trendy short hairstyles of the 1920’s, as well as the deaths of five of the sisters by 1920.

Rawleigh’s Tonic Compound

According to Rawleigh’s Good Health Guide (Almanac and Catalog) from 1935, Rawleigh’s Tonic Compound was suggested as a part of treatment for anemia, dizziness from weakness, neuralgia (if the patient is pale and weak), and colds. The tonic is described as being useful to get rid of wastes and build good blood, and even the purposes of the primary ingredients are listed: hypophosphites are “tonic in action” and help with anemia and malnutrition and iron builds red corpuscles (blood cells).

Some of these claims are more realistic than others. Iron is actually quite important for healthy blood, as proteins containing iron are crucial for storing, transporting, and using oxygen. Iron deficiency is currently the most common nutrient deficiency in the world, and iron supplements are quite commonly used. At least that element of Rawleigh’s Tonic Compound would actually be useful in treating anemia (specifically iron-deficiency anemia, which is the most common type), and could help with dizziness depending on the cause.

The other components, however, were probably not very effective for their advertised purposes. Hypophosphites, the primary advertised ingredients on the bottle, are compounds containing the hypophosphite ion and other elements, including sodium, manganese, potassium, and calcium, all ingredients in the tonic. Hypophosphites were actually theorized to be a cure for tuberculosis in the mid-19th century by Dr. John Francis Churchill. He believed that this form of phosphorous would attract oxygen and that increasing oxidation would cure tuberculosis. While this was quickly disproved, it began a trend of advertising hypophosphites in tonics and elixirs, and salesmen would likely have promoted Dr. Churchill’s claims without mentioning that he was actually wrong. While it was unlikely that these compounds actually had their intended effects, manganese hypophosphite and sodium hypophosphite at least are classified as “generally recognized as safe” by the USA Food and Drug Administration, so they were not likely to be entirely damaging either.

However, strychnine, another listed effect, is quite unhealthy. In fact, it is a highly toxic compound used as a pesticide, specifically for small vertebrates (such as birds and rodents). According to the CDC, only a small amount is needed to cause severe effects, and strychnine poisoning can be fatal. The toxic effects of strychnine have been known for centuries and this Rawleight’s Tonic Compound bottle lists the amount of grain Strychnine Alkaloid in a maximum dose, which implies a recognition that it was a poisonous substance. Luckily for the consumers, it seems that Rawleigh’s tonic compound was not generally lethal, despite the poisonous ingredient, and it was a very successful product for many years.

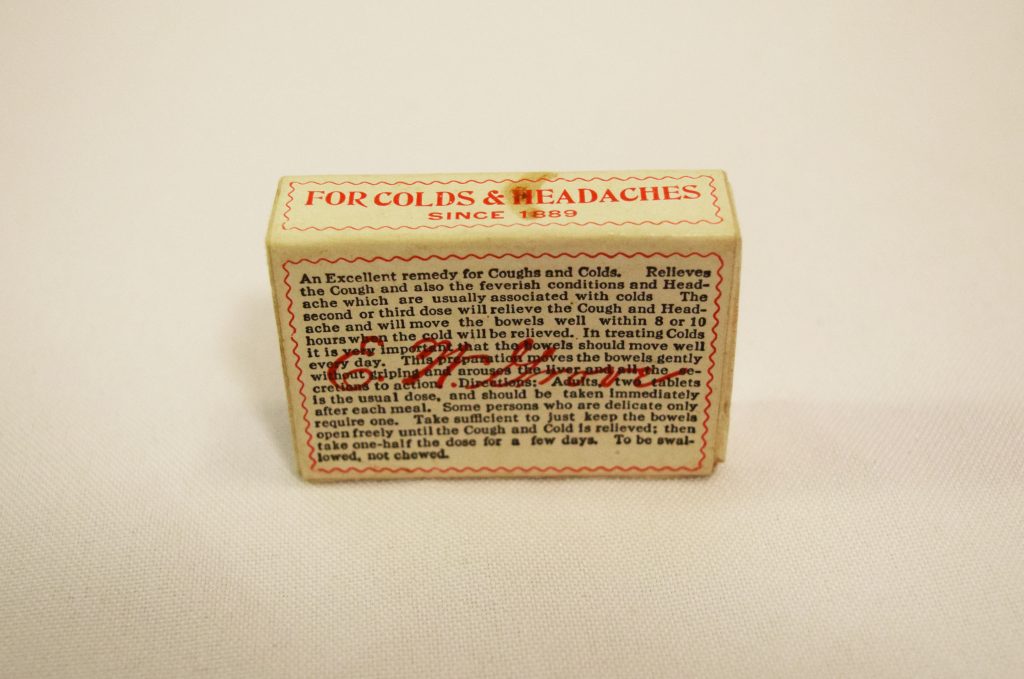

Bromo-Quinine Laxative “For Colds and Headaches…”

While these Bromo Quinine pills, like all other patent medicine, would not actually have had the entire effects that they promised, they are interesting in that they do contain some real medicinal ingredients that are still used to this day.

One of the two primary ingredients advertised in these pills is quinine, which is a legitimate medicine used to treat malaria. In fact, it has been used as a cure for the illness in Europe since the early 17th century, and remained the primary cure until new medications with less potential side effects came into prominence in the mid0-20th century. Quinine is still sometimes used, especially in cases of malaria strains that are resistant against certain other drugs. Antimalarial drugs were actually how E.W. Grove built his company. While quinine was quite popular in the United States in the late 19th century, it was very bitter and unpleasant to consume. E.W. Grove came up with a solution called Grove’s Tasteless Chill Tonic which, while not entirely tasteless, was able to mostly mask the bitterness of the quinine. This proved to be very popular and the Paris Medicine Company was born. As an interesting sidenote, a solution found by the British in colonized India to the problem of quinine’s taste was to dissolve their quinine powder in soda water and then mix it with gin to mask the taste, creating the gin and tonic.

With the Tasteless Chill Tonic’s success, Grove’s company expanded, and he soon developed the Laxative Bromo Quinine tablets, which he marketed as a cold cure. Including quinine in the name was likely a very smart move in marketing, as quinine was known to be a legitimate medicine. However, quinine is only really medicinally functional for treating malaria, so it would not have done anything to cure a cold. It is unclear whether the “Bromo” portion of the name would have resonated in any particular way with consumers. However, bromine does function as a sedative, which likely would have resulted in a calmer feeling for the customer, but would also have done nothing to cure a cold and would have lead to negative neurological side effects with prolonged use. The one potentially useful ingredient listed on the front of the box was acetanilide. While this substance is no longer used due to harmful side effects, it was discovered that it was metabolized to paracetamol in the body. This substance otherwise known as acetaminophen (commercially available under names such as Tylenol) is effective and has less side effects, and is commonly used in modern times to treat a cold. Of course, getting one effective ingredient out of three is not a great ratio for medicine.

These Bromo Quinine tablets get even more concerning, however, with the less prominently advertised ingredients. The side of the box lists belladonna extract and stramonium extract amongst the ingredients. Atropa belladonna, also known as deadly nightshade, is a very toxic plant which has been used as a poison for millennia, including (according to rumours) by two Roman Empresses and by Macbeth, King of Scotland. While Belladonna has historically been used in herbal medicine, it is not recommended for consumption as it is very, very toxic. Datura stramonium, also known as devil’s snare, while historically used as an anaestheic and a painkiller, is also a toxic plant, and there is a high risk of a fatal overdose if people consume it without an adequate understanding of its effects. While both of these substances were probably used, like bromine, to reduce pain, they were also very dangerous and an error in the dosage of the tablets could have led to some very serious side effects.

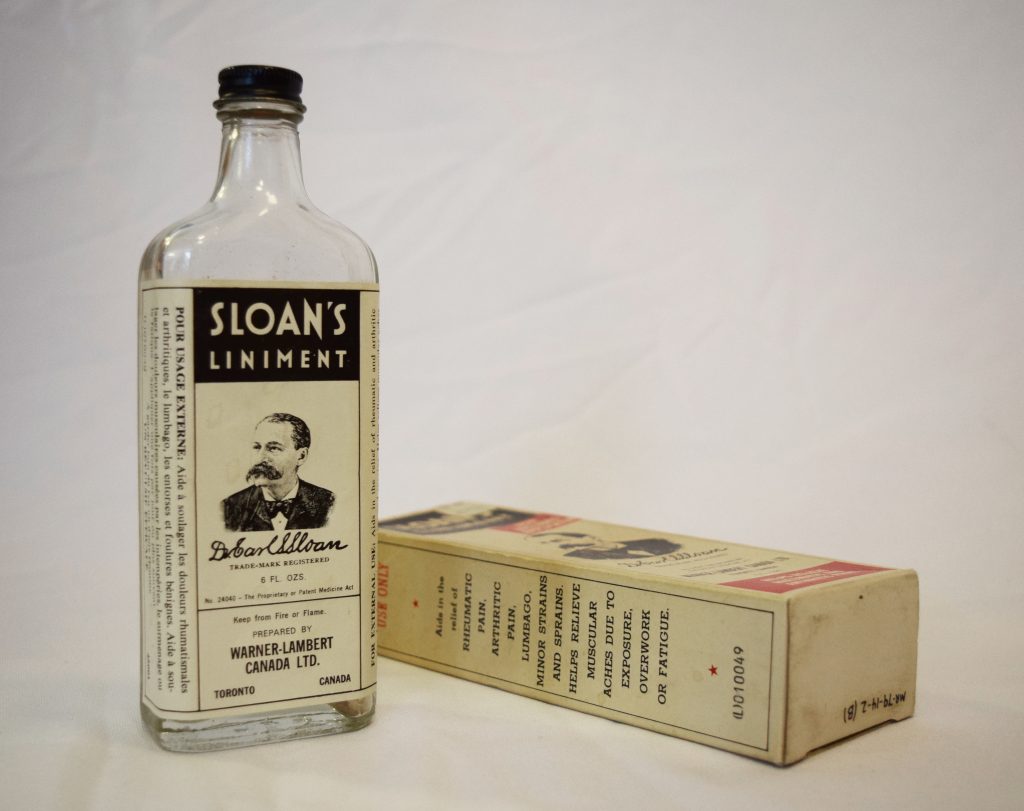

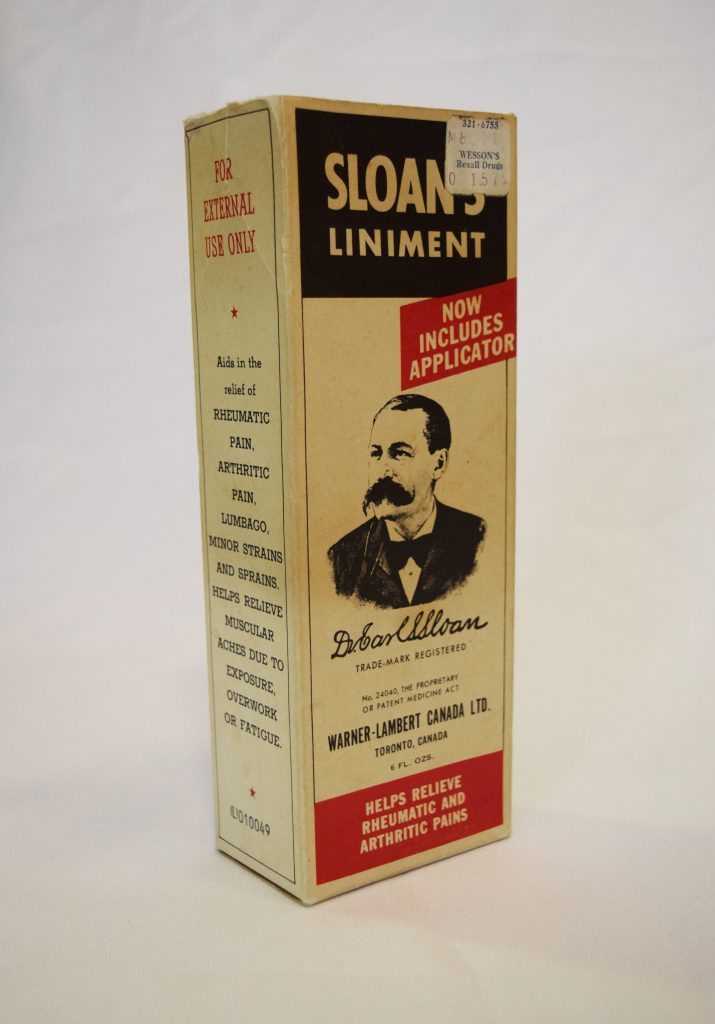

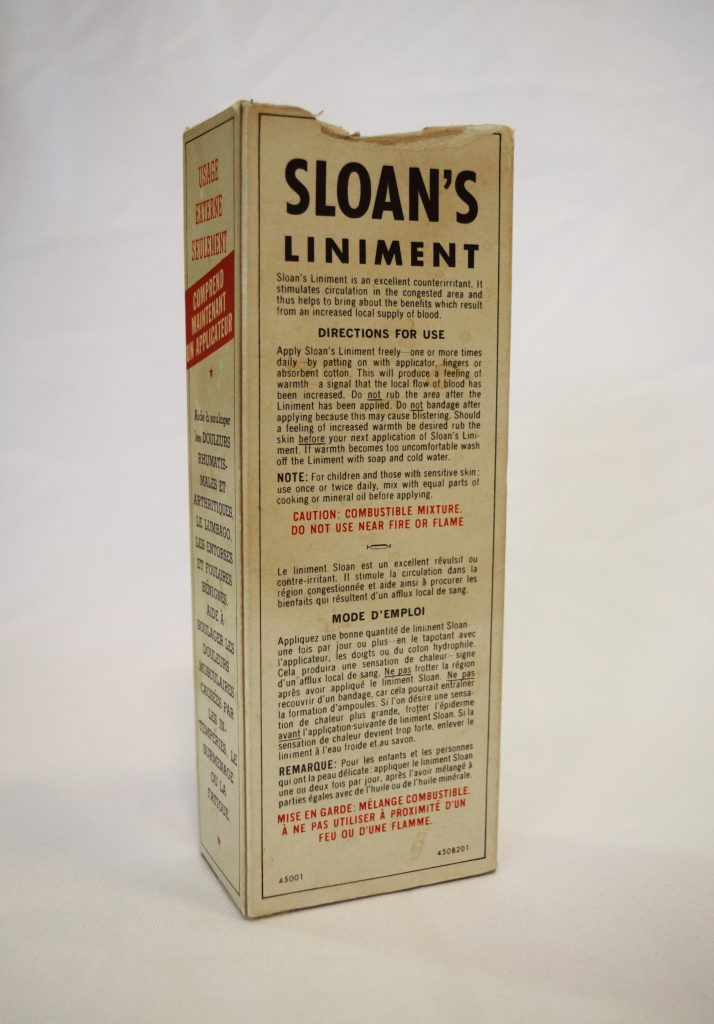

Sloan’s Liniment

Andrew Sloan, an Irish immigrant, was a horse harness maker by trade. However, he developed skills in animal care and eventually became a self-taught veterinarian known as “Doc Sloan.” In the 1850’s or 1860’s, he created a liniment to reduce joint pain and inflammation in working horses. This liniment was widely successful as horses were very central to American life and business in the late 19th century. In the 1870’s, Andrew’s son Earl headed to St. Louis to sell the horse liniment there. As the story goes, someone decided to try putting the liniment on their own back and discovered that it worked just as well for human aches as for horses. Earl quickly began to advertise the liniment in newspapers and expand into this new market.

In the mid-1880’s, Earl refined and patented the liniment and he began to grow his new business. Within the next 20 years the company continued to grow, and in 1904 Earl moved manufacturing operations to Boston. He incorporated the business as “Dr. Earl S. Sloan, Incorporated.” Like his father, he never received actual medical training or officially received the title Doctor. However, patent medicines were all about advertising, and an average person would likely have simply taken his title as a sign of credibility. By 1907, the company had gone international, as sales were reported in South America, Australia, Europe, and Canada.

In 1913, the company was sold to William R. Warner & Co., which merged with Lambert Parmacal Company in 1955 to form Warner-Lambert Pharmaceutical Company. The latter is the name that is on the box, which means that this bottle must have been produced after 1955. That means that the product survived major changes to regulations in both Canada and the United States. The 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act in the United States required medicines to list their actual ingredients, not contain anything proven to be addictive, and no longer claim to cure things they were not proven to cure. In the late 1920’s, Canada passed a food and drug act that limited what medicines could claim to cure. This product likely survived because it does not claim to cure anything so much as relieve some pain, and because the active ingredient, capsaicin (also the active component of chili peppers) does have analgesic properties. Sloan’s liniment can actually still be found on the websites of major retailers including Walmart and Amazon. According to many reviews on Amazon, it is no longer as strong or effective as it used to be, probably because the capsaicin concentration has been reduced over time.

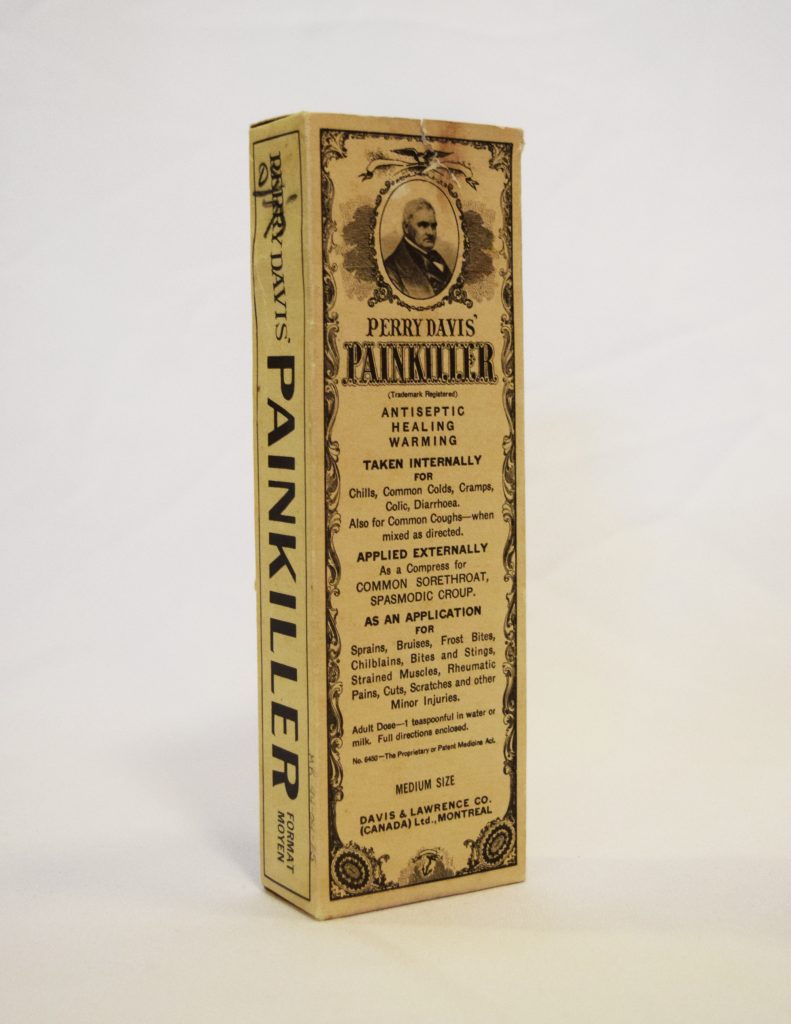

Perry Davis Pain Killer

In the late 1830’s, failed inventory Perry Davis fell ill and decided to mix a concoction to ease his pain. He recovered from his illness and decided to try to market this one invention that had actually worked: his painkilling elixir. For the first time ever, one of his inventions was an astounding success. Perry Davis’ painkiller was the first general painkiller in the United States or Canada, and we may actually owe the general term “painkiller” to him as he trademarked the name “Pain Killer” when he began to sell his product.

According to early advertisements, this product was originally called “Perry Davis’ Vegetable Pain Killer.” This particular bottle, however, seems to be a later iteration that has dropped the “vegetable” portion of the name, likely because this product was not at all vegetable-based. Early claims of “A purely vegetable medicine” were not at all fact-based, as the product definitely contained ethyl alcohol, opiates, and camphor, and maybe some vegetable extracts. Despite this, the bottle inside the box does have word “vegetables” embosed on the side of the glass bottle as a subtle throw back to its roots.

Camphor is absorbed through the skin and can produce a warm or cold sensation depending on how vigorously it was applied. This sensation would have provided the illusion of healing and a distraction from the pain when applied externally, although its actual analgesic properties are quite mild. Interestingly, camphor is the primary active ingredient in Vick’s VapoRub as it has cough suppressant properties. Opiates, drugs derived from opium, are functional painkillers, but they also have a high abuse potential and can have serious withdrawal symptoms. Ethyl alcohol, otherwise known as ethanol, is the type of alcohol that people can drink. It does not really have medical uses when consumed, but in low doses it is a depressant that causes euphoria and reduces anxiety, which is to say that it would cause a temporary improved mood in people who consumed the painkiller. Low doses are generally not toxic, although long term use can lead to liver damage. In general, mixing opiates with alcohol does increase the risk of life-threatening side effects, particularly respiratory depression, especially in seniors, which could potentially have been a problem. Overall, this substance would have probably been effective at masking pain, but it clearly was not the mixture that was advertised.