For generations, the Indigenous people in what is now known as British Columbia fished and put away stores to feed them through the winters. Fishing rights were granted and passed down through potlatch naming ceremonies. In 1827, the Hudson’s Bay Company established Fort Langley on the Fraser River. The Fort traded in more than furs, they processed salted salmon which they packed and shipped in barrels as an export product to the Hawaiian Islands.

The Fort purchased the salmon from the Indigenous People who fished the Fraser River. Hawaiian men were employed by the Hudson’s Bay Company as crew and then stayed to build and work at Fort Langley. The men from the Pacific Islands became known as the kānaka from the Polynesian word for person.

For generations, the Indigenous people in what is now known as British Columbia fished and put away stores to feed them through the winters. Fishing rights were granted and passed down through potlatch naming ceremonies. In 1827, the Hudson’s Bay Company established Fort Langley on the Fraser River. The Fort traded in more than furs, they processed salted salmon which they packed and shipped in barrels as an export product to the Hawaiian Islands. The Fort purchased the salmon from the Indigenous People who fished the Fraser River. Hawaiian men were employed by the Hudson’s Bay Company as crew and then stayed to build and work at Fort Langley. The men from the Pacific Islands became known as the kānaka from the Polynesian word for person.

Many of the Kanaka men settled and married women from the Kwantlen and Musqueam nations. Kwantlen Traditional Territory extends from Richmond and New Westminster in the west, to Surrey and Langley in the south, east to Mission, and to the northernmost reaches of Stave Lake. The Kwantlen are a Stó:lō people. In early European records, the Kwantlen people are referred to as the Quoitlen, Quaitlines and various other spellings.

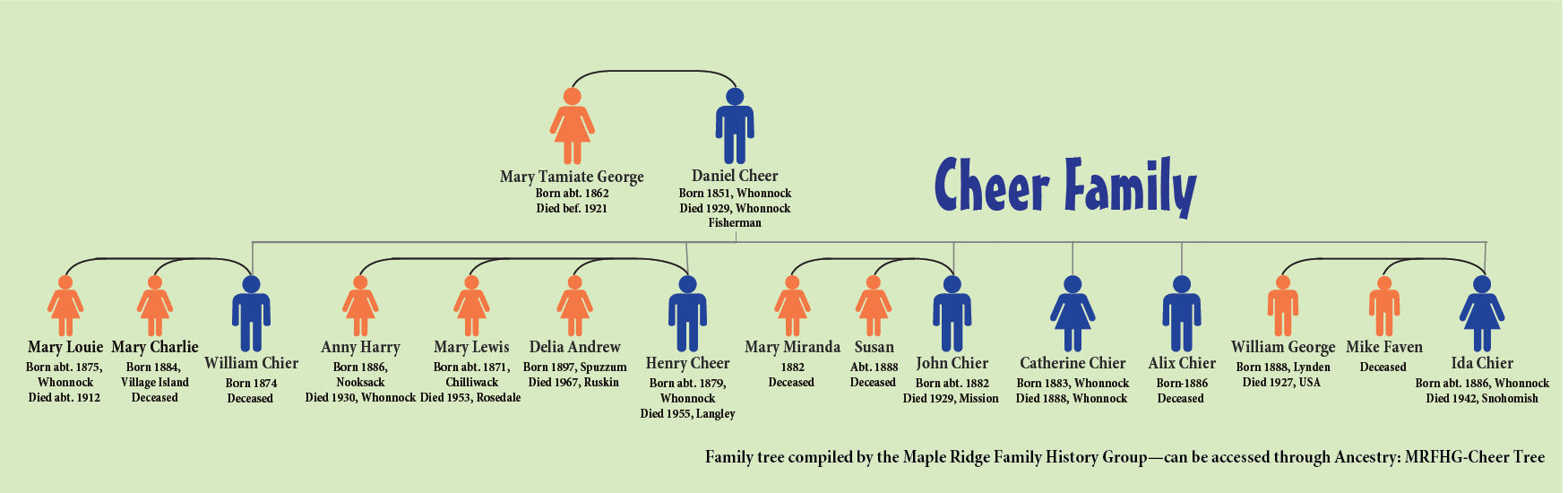

The Kanakan men had the same civil rights as other newcomers and could vote or pre-empt land, provided they became naturalized as British citizens. Despite the divisions caused by the Federal Indian Act of 1876 that dictated that Indigenous women, and thereby their children, who were married to non-Indigenous men lost their right to live on the reserves and restricted from access to their traditional fishing spots, the Cheer family were part of the larger community of Kwantlen and Hawaiian people — they had migrated from the Langley side of the Kwantlen Traditional Territory to the Whonnock side between 1881 and 1891.[i]

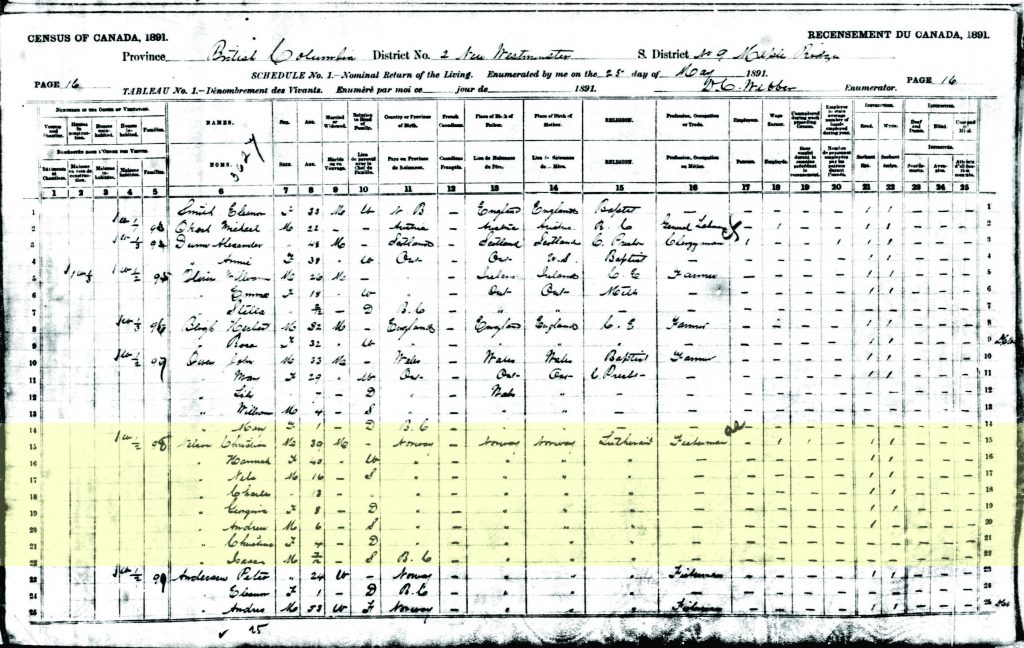

British Columbia born Daniel Cheer (also Chier) listed his occupation as fisherman in the 1891 Census. His father was born in Hawaii (named the Sandwich Islands by Captain James Cook in 1778). Daniel’s mother Katherine was born in British Columbia and is living with the family. Both of sixty-year-old Katherine’s parents were born in BC. Forty-year-old Daniel lived in a three-room, 2 story, wooden house with his wife Mary and their children: William, Henry, John, Alex, and Ida. Daniel’s brothers Joseph, thirty-one, and Thomas, twenty-nine, live with the family and are also fishermen. British Columbian born Mary was twenty-nine years old. Both of Mary’s parents were born in British Columbia.[ii]

[i] Cheer family identified by the Stó:lō Research and Resource Management Centre, 1881 Canadian Census, Coast of Mainland, New Westminster, British Columbia; Sub district A&B Quoillin (Kwantlen), Roll: C_13284; Page: 98; Family No: 715.

[ii] 1891 Census of Canada. Library and Archives Canada. Census Place: Maple Ridge, New Westminster, British Columbia, Canada; Roll: T-6290; Family No: 125.

The 1891 census also captured more recent immigrants such as thirty-nine-year-old John Christian Nelson, his forty-year-old wife Hannah and their six children (Nels, Charles, Georgina, Andrew, Christine, and Isaac) who were living in a two-room one story house. The Nelsons had all been born in Norway with the exception of seven-month-old Isaac, born in 1890, after their immigration to Canada in 1888.[i] According to family lore, Christian brought his fishing equipment with him and was one of early halibut settler fisherman in BC.[ii]

[i] Nelson family, 1891 Census of Canada, Library and Archives Canada, Series RG31-C-1. Statistics Canada Fonds. Roll: T-6290; Page 16, Family No: 98, Lines 15–22.

[ii] “Jacob I. Nelson”, profile compiled by the North Pacific Cannery.

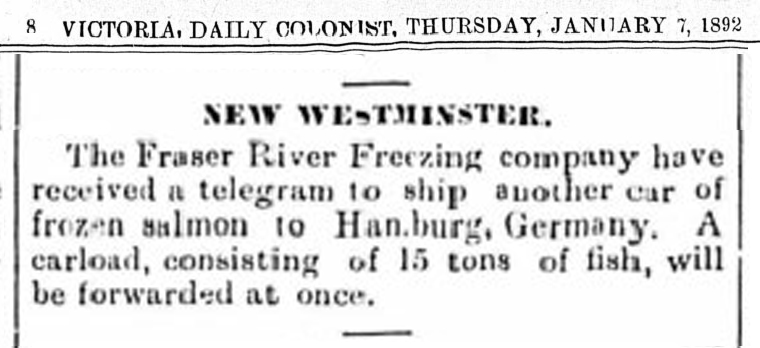

The Port Haney wharf seen from the Fraser River circa 1900. Haney House can be seen at the right on top of the hill. The Fraser River Freezing Company was at the foot of 224th on the Fraser. The 1891 William’s British Columbia Directory describes the company as a large establishment for freezing salmon.

CREDIT: Maple Ridge Museum & Archives, P00407

Salmon rose to prominence after fish freezers were built on the Fraser River in 1886.[i] In 1890, 150 licenses were granted to canneries, farmers, and fishermen for freezers. The Vancouver Daily World reported that Mr. Samuel Wilmot, federal superintendent of fish culture, felt the reduced fish freezer license fee for farmers was correct while acknowledging that the canners felt “dissatisfied with the discrimination against themselves.”[ii]

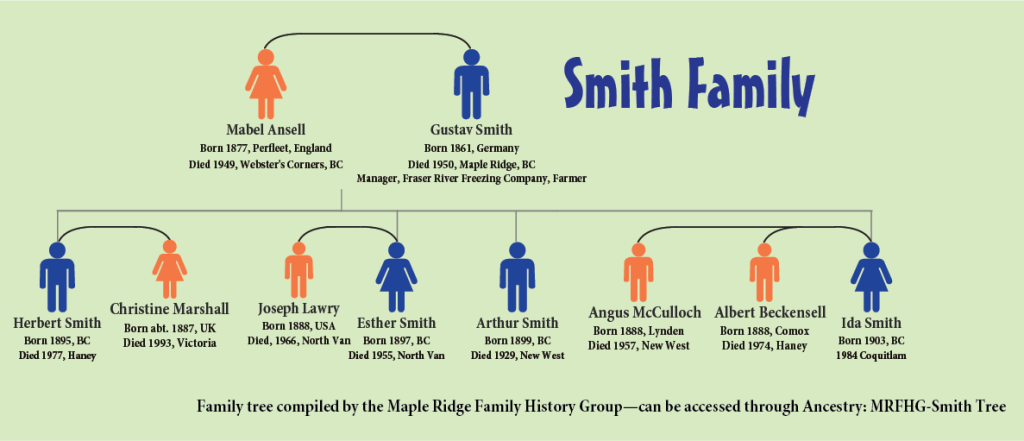

German-born Gustav Smith listed his occupation as a farmer in the 1891 census. Smith was thirty-years-old, single, a member of the Presbyterian Church of Canada. He lived in a three room, one-story wooden house. He was also the manager of the Fraser River Freezing Company’s fish freezer as noted in the 1891 William’s British Columbia Directory.[iii] Gus Smith immigrated to Canada in 1882[iv] and first appears in the directories in 1889—the William’s British Columbia Directory records an Augustus Smith as a fisherman for the Fraser River Freezing Company in Port Haney. “Gustav Smith fished on the Fraser when salmon brought 3 cents each, but the money he made in the fishing season helped to see the family through the winter.”[v] Fish freezing was a service provided by the existing ice making plant in Port Haney. The fish freezer is noted in the directory as a feature of Port Haney until 1901, however, the last mention of Gustav Smith as the manager is in the 1898 directory.

In 1889, in response to concerns of over-fishing, the number of fishing licenses on the Fraser was limited to 500. The majority of the licenses 350, went to the canneries in proportion to their capacity.[i] In response, some cannery owners built dummy canneries to obtain additional fishing licenses.

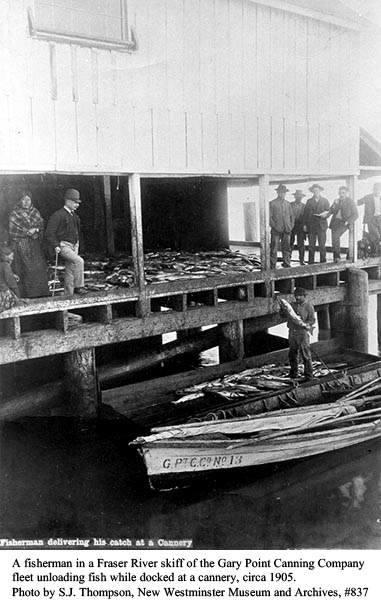

The year of the census also brought a change to the salmon canning industry. Henry Ogle Bell-Irving founded the Anglo British Columbia Packing Company—acquiring the Annieville Cannery, British American Cannery, Canoe Pass Cannery, Wadhams Cannery, Phoenix Cannery, Garry Point Cannery, and the Britannia Cannery. With the consolidation the Anglo British Columbia Packing Company now packed slightly over twenty-five percent of all salmon, making it the largest packer of sockeye salmon in the world.[ii] The commercialization of the fishing industry was well on its way.

[i] Douglas M. Swenerton, A History of Pacific Fisheries Policy, (Canada. Department of Fisheries and Oceans, 1993) 15.

[ii] “Timeline”, from Tides to Tins, Gulf of Georgia Cannery, 2021, http://tidestotins.ca/timeline/.

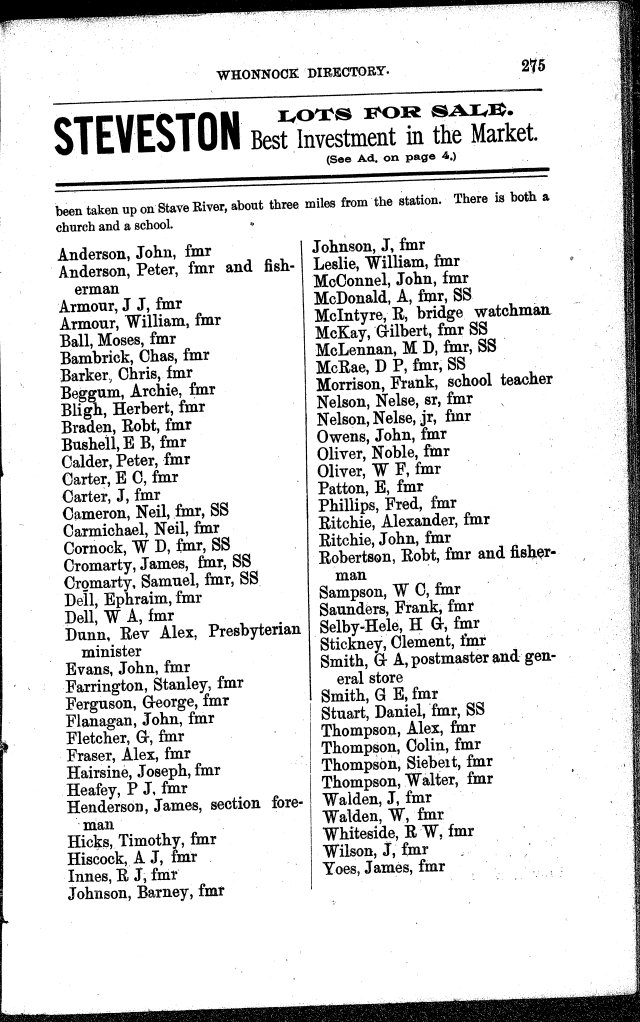

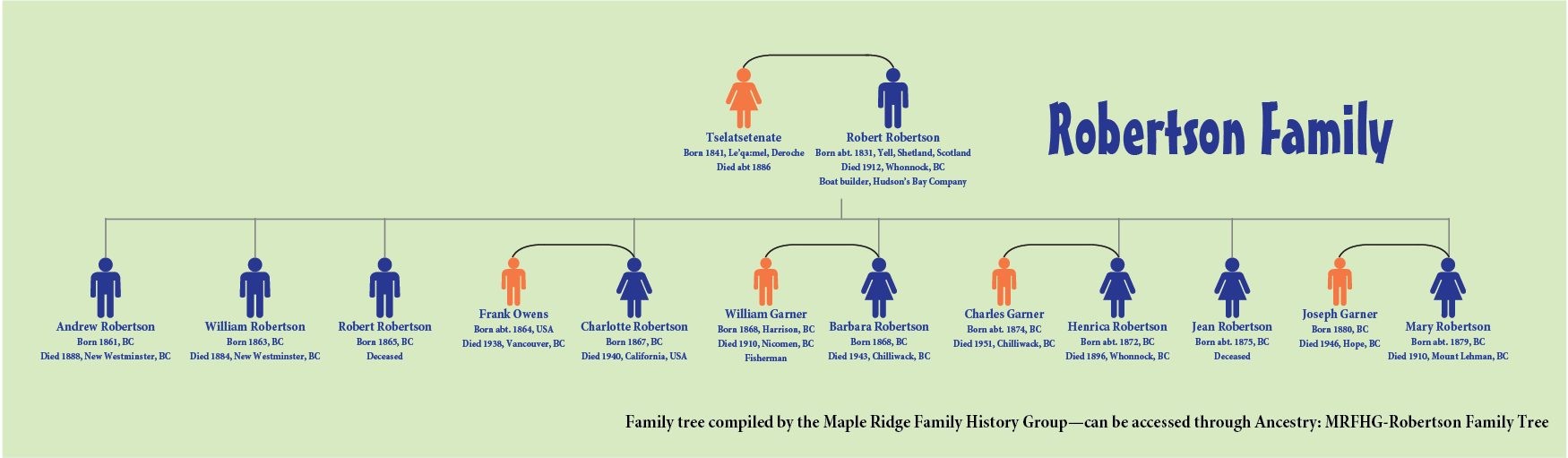

A diary written by Maple Ridge resident John Williamson mentions numerous people who at first glance do not appear to be involved in fishing. Robert Robertson was a retired Hudson’s Bay Company employee who settled in Whonnock, taking up land on the Fraser about 1860 with his wife Tselatsetenate.[i] Tselatsetenate was a member of the Stó:lō nation. He worked as a boatman, rowing people and freight up and down the Fraser River.[ii] In 1891, Robert Robertson is recorded as a sixty-year-old widowed, boat builder from Scotland. Robertson was a skilled carpenter who built and repaired boats. He likely built what was known as the Fraser River skiff, based on the 1860s bateaux style boats used by the Hudson’s Bay Company. He lived in a four-room, one story, wooden home with his four British Columbia born daughters; Barbara, Hennie, Jean, and Mary.[iii] The 1891 Williams’ British Columbia Directory tells a different story—Robertson is listed as a farmer and fisherman.[iv]

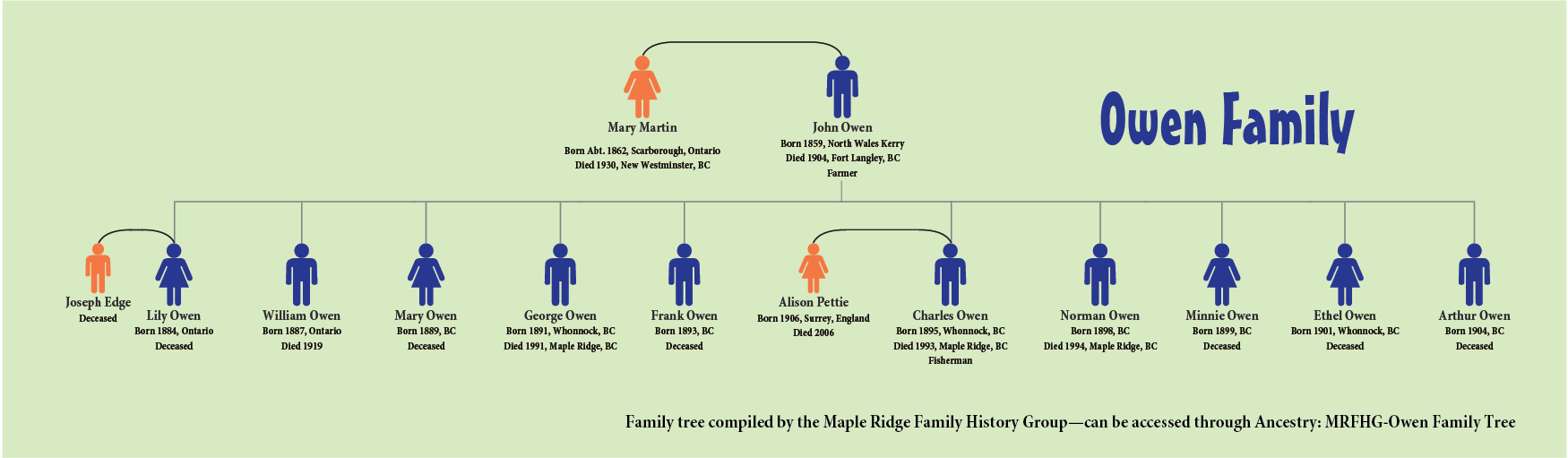

Williamson reports in his July 27 entry that John Owen, was thought by the other fisherman of trying to gain favour with the Bon Accord Cannery. [v] Owen was born in Wales. In 1891 he lists his occupation as farmer. He is living with his Ontario born wife Mary, and children, Lily, William, and Mary.[vi]

The Bon Accord cannery was located less than a kilometer above the south end of New Westminster at what is now known as Port Mann. Built in August 1877 by merchant and politician Ebenezer Brown, with investors from London, England under the company name English & Co., the cannery was the second one built by Brown.[vii] By 1891, the cannery was owned by Alexander Ewan and Daniel J. Munn. With 26 boats and 144 workers the cannery produced 375,552 1-pound cans of salmon.[viii] When Michael Davitt, the Irish republican activist, visited British Columbia in 1891 he visited the salmon canneries in New Westminster owned by Alexander Ewan. Davitt claimed to have seen the accounting books and reported that the canneries employed over 200 Indigenous workers. The fishermen earned $900 (about $26, 836 in 2021 dollars) in six weeks. The men earned two dollars (about sixty dollars in 2021 dollars) a day and the women earned one dollar and twenty-five cents (about thirty-seven dollars in 2021 money) a day for work in the cannery.[ix]

[i] Sheila Nickols (ed), and others, Maple Ridge: A History of Settlement, (Maple Ridge: Canadian Federation of University Women, 1972) 2.

[ii] Fred Braches, “Robert Robertson & Tselatsetenate,” Whonnock Notes # 7, 10.

[iii] Robertson Family, 1891 Census of Canada, Library and Archives Canada, Series RG31-C-1. Statistics Canada Fonds. Roll: T-6290; Page 17, Family No: 100, Lines 2–6.

[iv] 1891 Williams Official British Columbia Directory, R.T. Williams: Victoria, page 275.

[v] Transcription, Fred Braches, “John Williamson’s Diary Revisited,” Whonnock Notes #13, Fall 2005, 34.

[vi] Owen family, 1891 Census of Canada, Library and Archives Canada, Series RG31-C-1. Statistics Canada Fonds. Roll: T-6290; Family No.97.

[vii] “New Westminster District”, Daily British Colonist, 3.

[viii] Annual Report of the Department of Fisheries, (Ottawa: Dominion of Canada, 1891) 168.

[ix] “Michael Davitt’s Views,” The Vancouver Daily World, April 26, 1892, 4. Second source: “How much is a dollar from the past worth today?” MeasuringWorth, 2021. URL: www.measuringworth.com/dollarvaluetoday/

Read more…

We acknowledge that the land on which we live, work, and play is the traditional and unceded territory of the Katzie First Nation and the Kwantlen First Nation Peoples. We respectfully honour their traditions and culture.