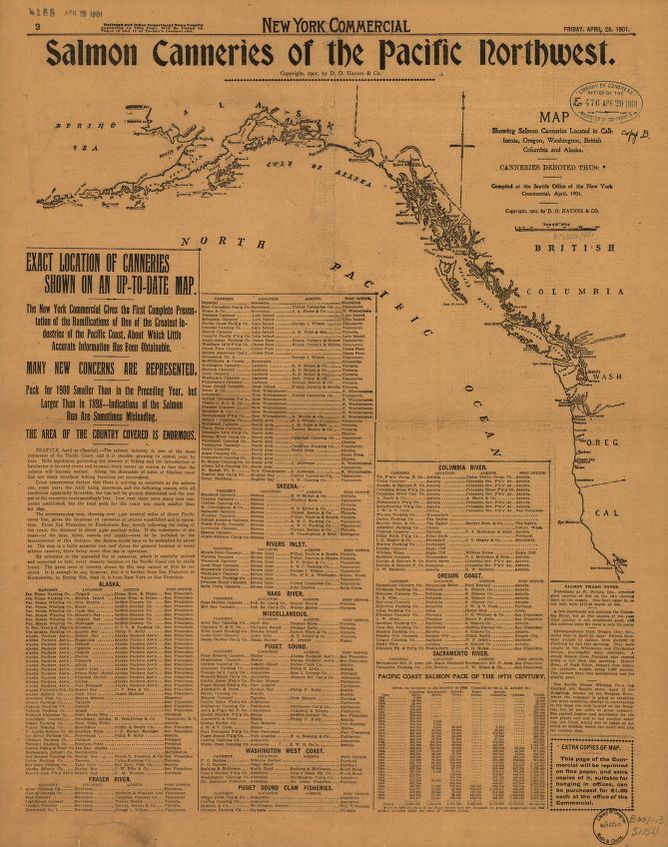

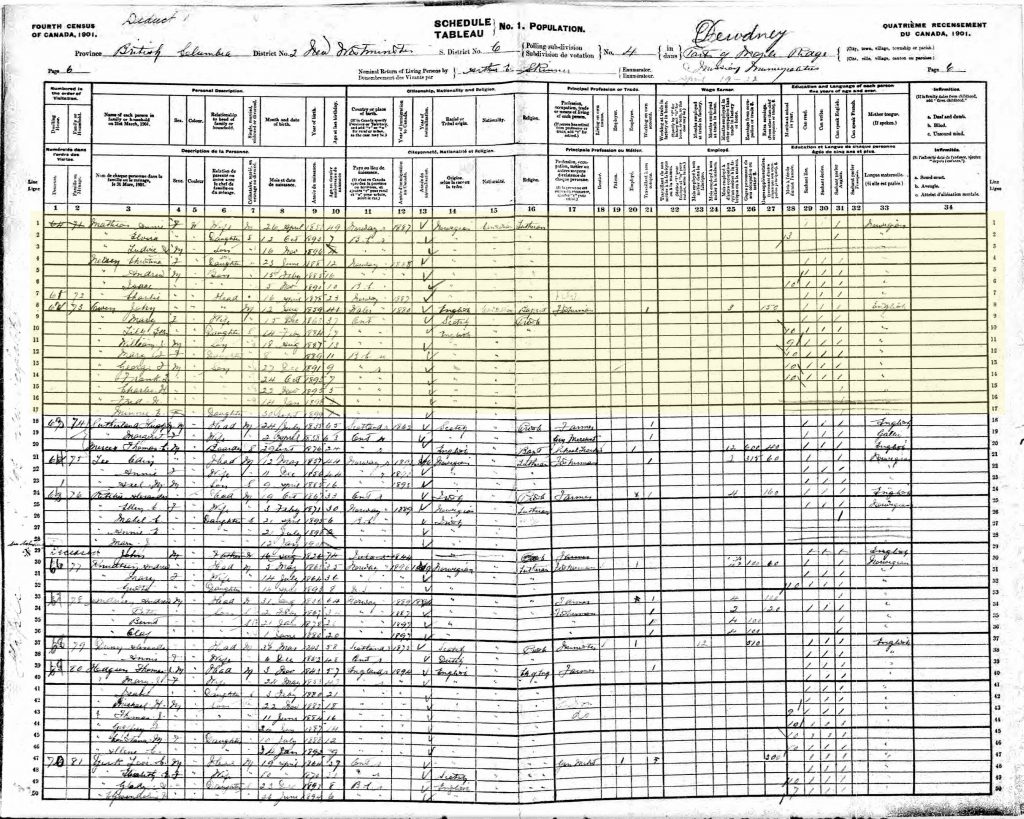

Ten years later, in the 1901 census, the fortunes of some of the fishermen had changed. In 1894 the Fisheries Act was amended making it illegal for Indigenous people to catch fish for commercial purposes without a commercial fishing permit and license. Only 14 men listed their primary occupation as fisherman out of the total population of Maple Ridge of roughly 1,066 people in 1901. It is impossible to determine how many people were employed as cannery workers from the census.

In 1901 the British Columbia Fisheries Act established the Board of Fishery Commissioners & BC Department of Fisheries. An overabundance of canned salmon created an environment for the formation of the BC Packers Association in 1902—an amalgamation of thirty-nine independent canneries.

Frank Devlin, Indian Agent for the Fraser River Agency, noted that the Indigenous people living on the Langley and Whonnock reserves had shifted their focus to mixed farming and working for the canneries during the fishing season.[i] Also noted in the report is a “severe competition in the labour market” in the fishing industry from the Japanese fishermen. This shift in the labour market is evident in the 1901 census—the primary occupation listed is farming followed by people employed at a brickyard.

[i] Annual Report Of The Department Of Indian Affairs For The Year Ended June 30 1902, (Ottawa: S.E. Dawson, 1901), 230.

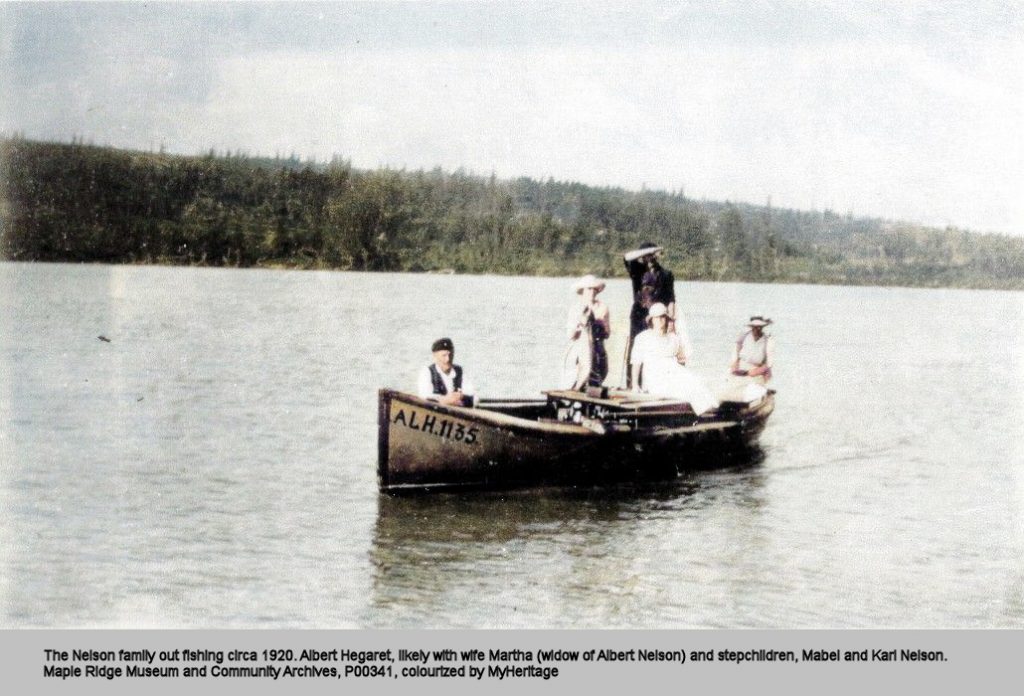

Maple Ridge Museum and Community Archives, P00341, colourized by MyHeritage

Despite listing his occupation as a fisherman on the voters list in 1898, Daniel Cheer’s occupation in the census is farmer, working on his own account, spends three months in a different occupation from farming, and his extra earnings are $125.[i] Daniel Cheer and his family are enumerated twice in the 1901 census, in the census recorded by census taker Arthur Skinner and in the census of the Whonnock Reserve, part of the Kwantlen First Nation.

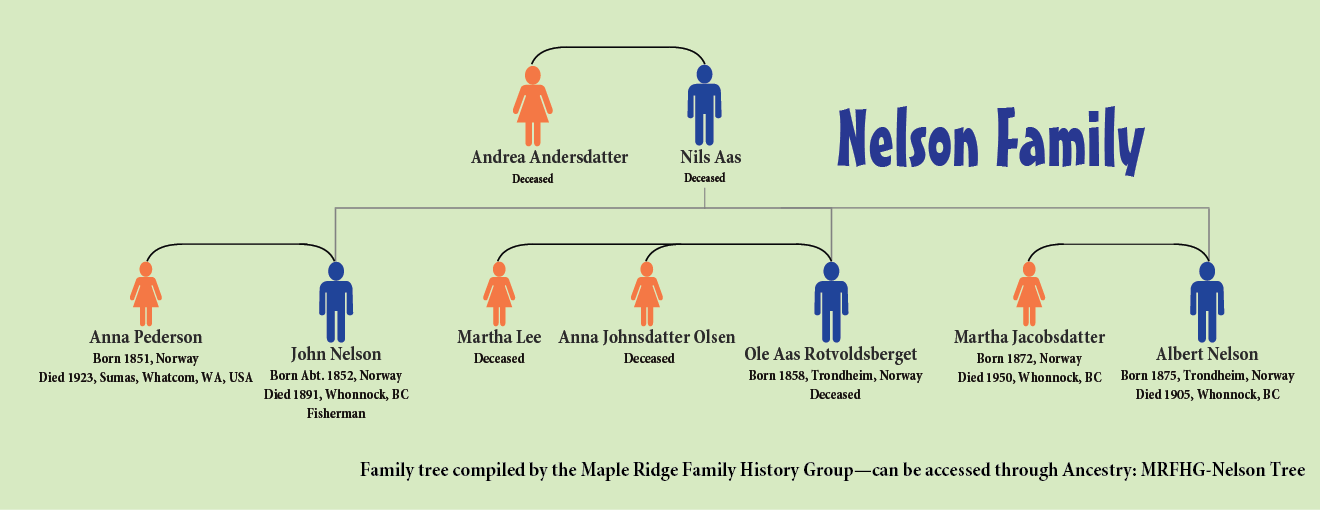

The fishing industry in Maple Ridge was interconnected with surrounding communities and continued to draw people to the area. John Christian Nelson’s brother Ole emigrated from Norway in 1891 although his family settled in nearby New Westminster. Thirty-six-year-old Ole and his sixteen-year-old son, Andrew both list their occupation as fishermen.[ii] Ole’s twenty-three-year-old son Carl was employed as a fisherman in Delta.[iii]

The fishing industry covered a broad scope of occupations. Ole Nelson’s sons were involved in a variety of ways. Sons, Carl and Sverre Nelson were also employed as fish collectors.[iv] Son Alex was a fish buyer.[v] By 1901 Robert Robertson was living with his daughter Barbara and her family. Both Robert and his son-in-law William Garner listed their occupations as fisherman.[vi]

[i] British Columbia. Legislative Assembly. (1899). Supplementary List of Persons Entitled To Vote In The Dewdney Riding Of Westminster Electoral District. 8TH June, 1898. [L]. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0064006

[ii] Ole Nelsen Family, 1901 Census of Canada, Library and Archives Canada, Series RG31-C-1. Statistics Canada Fonds. Microfilm reels: T-6428 to T-6556; page 8, Family No: 69, Lines 7-11.

[iii] Charlie O Nelson, 1901 Census of Canada, Library and Archives Canada. Series RG31-C-1. Statistics Canada Fonds. Microfilm reels: T-6428 to T-6556; page 6, Family No: 59, Line 47.

[iv] Marriage of Carl Olaf Nelson, 47, and Anna Carolina Knutsen, 20; Carl states he is fish collector, British Columbia Marriage Registrations (British Columbia Archives), Registration Number: 1925-09-292096, BC Archives Mfilm Number: B13750, GSU Mfilm Number: 2074320. Event Date: June 25, 1906. Second source: Sverre Andrew Nelson, age 54, Informant wife Mary Regina Nelson, British Columbia Death Registrations (British Columbia Archives), Registration Number 1936-09-522708; BC Archives Mfilm Number: B13158; GSU Mfilm Number: 1953022. Event Date: December 17, 1936. Bowell Funeral Records Database: S. Bowell & Sons, 1936 Record No 274. http://www.nwheritage.org/bowell/bowel.

[v] Axel Oswald Nelson, age 49, Informant his daughter Ruth E Pedersen, British Columbia Death Registrations (British Columbia Archives) Registration Number: 1941-09-584552, BC Archives Mfilm Number: B13170, GSU Mfilm Number: 1953630. Event Date: January 25, 1941. Second source: Bowell Funeral Records Database: S. Bowell & Sons, 1941 Record No 28. http://www.nwheritage.org/bowell/bowel.

[vi] Robert Robertson, 1901 Census of Canada, Census Place: Dewdney, New Westminster, British Columbia; Page: 7; Family No: 83, Library and Archives Canada, Series RG31-C-1. Statistics Canada Fonds. Microfilm reels T-20326 to T-20460. Second source: Death registration for Robert Robertson. British Columbia Death Registrations (British Columbia Archives), Reference ID: 26322, BC Archives Mfilm Number: B13090, GSU Mfilm Number: 1927118.

The newspapers started to report that fishermen and canners were not in agreement over the price of fish in May 1903. The canners offered a flat rate of 12 cents per fish or an alternative offer of a sliding scale of “20 cents for 2,400,00 fish; 18 cents for 3,000,000 fish; 16½ cents for 3,600,000 fish; 15 cents for 4,200,000 fish; 13½ cents for 4,800,000 fish; 11½ cents for 6,000,000 fish; and 11 cents for 6,600,000 fish.“[i] The White, Indigenous, and Japanese fishermen were united in their refusal. The British Columbia Fisherman’s Union issued a strike notice on July 1, 1903. The Province newspaper reported that “the fishermen here at Whonnock are standing by the Union” in the “Port Haney News” section of the July 3, 1903 edition, “and refuse to throw out a net till the trouble between the canners and fishermen is settled.” On the morning of July 13, the Japanese fishermen’s union signed an agreement to accept the canneries’ offer of fifteen cents for July and fourteen cents for August. The British Columbia Fishermen’s Union, representing the White fishermen, called their strike off late the same day.

The July 19, 1904 Province newspaper noted that John Owen had drowned on his way home. “Drowned at Langley: John Owen, Well Known Fisherman, Loses His Life in Salmon River.” He left his wife Mary a widow with ten children. Mary, understandably, had a tough time raising the family after John’s death.[ii]

[i] “Expected to Refuse Offers of Canners,” The Province, May 2, 1903, 1.

[ii] Senny Baker, interview by Ed Villiers, November 26, 1961, transcript held by the Maple Ridge Museum and Archives.

In 1905, Dominion Commissioner of Fisheries and General Inspector of Fisheries for Canada, Professor Edward E. Prince was appointed to head an inquiry in the fishing industry in British Columbia. As a result, new regulations were introduced in 1908. Increasingly fishing licenses were attached to the canneries and their fleets rather than independent fishers.[i] The inquiry also noted the lack of ability to enforce protective regulations in American waters that fed into the Fraser River were a major cause in the decline of salmon populations.

As well, the jobs in the canneries were becoming more mechanized. By 1909, the Smith Butchering Machine was installed in nine canneries along the Fraser River. Each machine replaced the butchering crew of thirty people with one skilled operator and a few assistants. The butchering crews were typically comprised of Chinese and Indigenous people.

[i] Dianne Newell, Tangled Webs of History: Indians and the Law in Canada’s Pacific Coast Fisheries, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993), 73–75.

Read more…

We acknowledge that the land on which we live, work, and play is the traditional and unceded territory of the Katzie First Nation and the Kwantlen First Nation Peoples. We respectfully honour their traditions and culture.