When the colonial government of British Columbia opened lands in the New Westminster district for settlement in 1858, the land north of Stó:lō [the Fraser River] was well-forested from the alpine to tidal marshes located two miles behind the ridge across from Derby. Logging was a necessary activity for early settlers, many of whom received government subsidies requiring them to clear certain amounts of land. Industrial logging arrived in Maple Ridge in the latter decades of the nineteenth century, and reached its zenith in the early twentieth. Crucial elements of these activities were the legal system which regulated the ownership of the forest resource and the technologies required to survey and extract the trees.

There are different ways of valuing the coastal forest, and these values influence the way the forest is used. Some pastimes and activities, like walking, fishing, collecting, or nature appreciation value the experience of the forest as a unique environment. But the key element of the forest – its trees – also has a cash value when it is processed and converted into industrial materials or household goods. Furniture, toys, paper, beams, shingles – all of these things come from the forest; demand for them puts a demand on the forest for trees. The price people are willing to pay for these things works its way back into the forest as a price on trees. Wood harvested for sale or use by the market is called timber. This display looks at how Maple Ridge’s forests were valued – how trees were “turned into” timber.

The first logging in the district occurred piecemeal as white settlers took up homesteads under the settlement acts of the colonial and Canadian governments. These pieces of law required settler families to meet specific maintenance targets in return for their title – or right – to property. The federal 1874 Free Homestead Act asked settlers to have cleared 15 acres of wooded land from the property claim within two years of it being granted. Wood collected in this way could be used on the homestead as fuel or construction material, but could not be sold without additional licenses under the provincial government. At Confederation, the provincial governments had retained a right to regulate property which extended to their management of natural resources, including forest lands. Forests were seen by early homesteaders as a hindrance and a threat to the household economy, even as the settlers depended on ready access to wood for the maintenance and operation of their farms. As commercial logging developed in the Fraser Valley, farmers came in to conflict with loggers, who were thought to profit unfairly from the resource.

Individuals and settler families were not the only people able to pre-empt land in early Maple Ridge. The area within 20 miles [32 kilometres] of the Canadian Pacific Railway was called the “Railway Belt” and was administered and surveyed by the federal government in the 1880s. Commercial logging was a developing industry throughout the province, but especially in the south coast areas with good transportation and water access. The forests on crown lands – areas over which the government claimed control – could be alienated using a few different kinds of ownership. As markets for wood products developed, there were three main legal instruments which granted private logging companies access to newly valuable timber: timber leases, timber licenses, and the outright purchase of land title.

In 1859, negotiations between Captain Stamp, a logging operator on the southwest coast, and the colonial government led to the first formal lease of timber. Timber leases separated the forest from the land by awarding loggers the right to extract wood from a specific crown tract for a 21-year period. Leases required that the logger operate a sawmill in connection with the land lien as a means of adding value to the industry – and the tax base. Licenses, like leases, permitted operators remove stands of timber on crown lands without acquiring title. Licensees were not required to operate a sawmill, and licensing was used by the government to allow small operators and hand-loggers to remove timber from crown lands. Stumpage fees were resource royalties paid to the government for the privilege of logging crown lands.

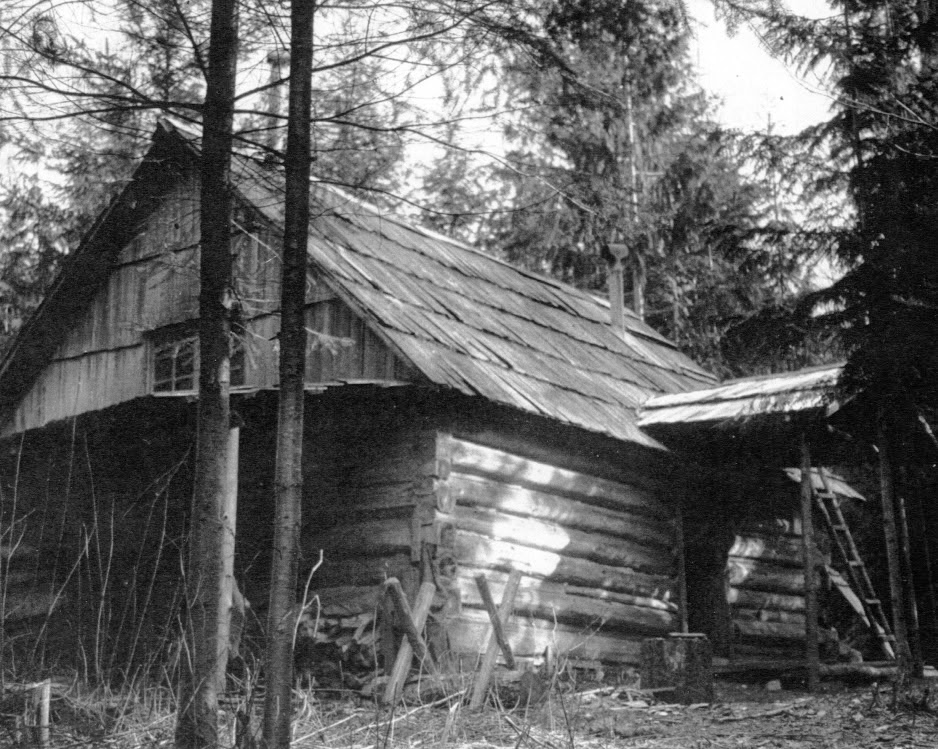

Loggers also speculated on timber values by purchasing large forested properties and holding them until supply and demand ran in their favour. Leases, licenses, and title were often combined in the portfolios of large companies. Big claim holders in Maple Ridge were the E.H. Heaps, with timber leases and a sawmill in Ruskin before 1912, and the Miami Corporation, which held timber leases – including the large Timber Berth W – around the face of Mount Blanshard. The Miami Corporation belonged to the Chicago-based Deering family, who had made their fortune by manufacturing agricultural equipment. These timber rights were contracted out to the Abernethy and Lougheed Logging Company, popularly “Allco”, which in the 1920s was the largest commercial logging outfit in the province of British Columbia. Both E.H. Heaps and Allco were “railway loggers”, using short-chassis locomotives to pull loads of lumber out of the woods from the cutting zones. Many camps with permanent and temporary structures dotted the woods, and the population of some of these could be in the hundreds.

In early years, a major concern of the backcountry operators was loss of logs in transport. Logs were floated to sawmills in large booms, but the onset of a freshet could break the boom and send unidentified logs ashore far away from their intended destination. The solution was to stamp each individual log with an ID number which corresponded to a government timber berth. This protected the investments of government claim holders, and helped the government assess stumpage fees.

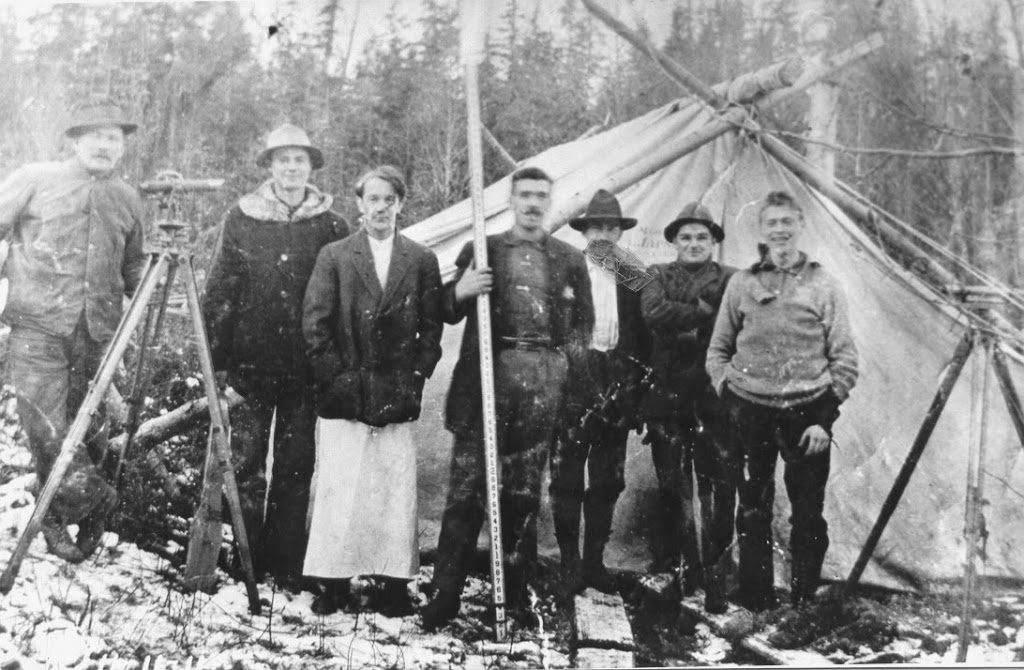

Before moving onto a piece of land, logging companies had to predict its value and profitability. Timber leases were only as valuable as their harvestable “board-feet”, a volumetric measurement of timber. Surveying was part of big business, and supported the extensive work camps, sawmills, railways, post offices, hostels, skylines and skid roads operated by large companies. Logging operations could be massive investments made by financiers in distant cities, and surveying reports were used by logging operators to leverage credit and plan out their operations years in advance. Teams “cruised” the timber berths, laying down chains to measure off a rectangular grid which could be used to organize a forest sample. The sampled distance between trees, the average girth of trees, and the distribution of species were applied to the grid’s subsections, allowing companies to estimate the recoverable board-feet for their claims and its market value, and weigh this against their expenses.

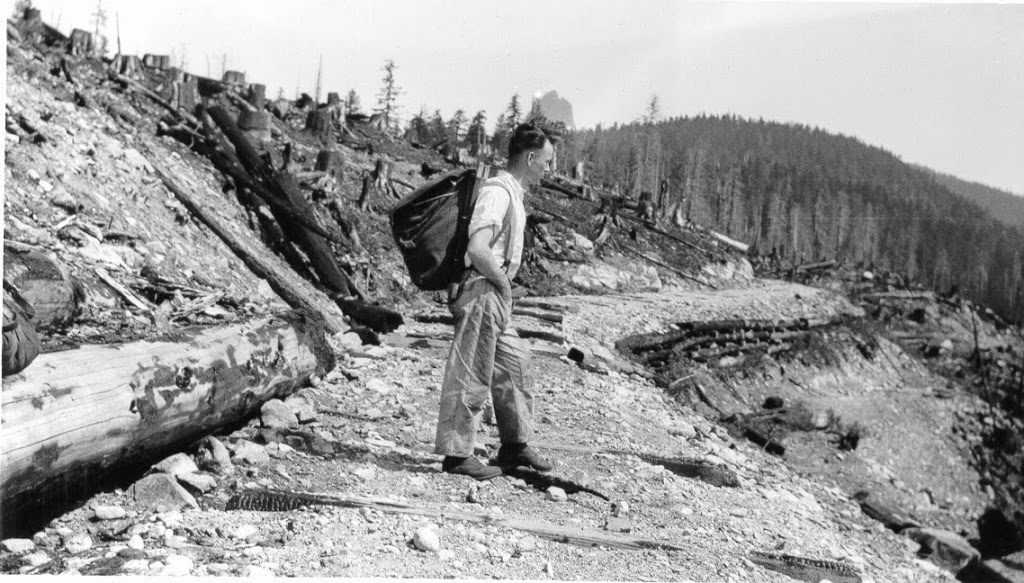

In Maple Ridge, big logging declined at the end of the 1920s. One problem was the frequent fires started by the activities of workers and their spark-setting locomotives, donkey engines and skyline rigging. Fires, if uncontrolled, could burn through accessible timber stands and immediately diminish a company’s earnings. There was also the risk of physical injury: moving large and unwieldy logs required unwieldy and dangerous equipment, and the nature of the work often found lumbermen off the ground or amid the saws. Workers unionized to lobby for better working conditions and higher pay. Local powerhouse Allco’s reliance on expensive heavy equipment, onsite labour, and American credit meant that as a whole the company was highly indebted. As the stock market fluctuated in the autumn of 1929, the value of Allco’s holdings decreased dramatically, making it difficult for the company to pay its workers and service its debts. Its holdings were sold off by 1930. Its successor, the Commercial Lumber Company, was burnt out of the remaining timber claims north of town in 1931 after a large fire broke out from the premises of a rival operation, Brown and Kirkland.

By the end of logging operations in the Alouette River Valley, the new forests science had grown out of logging operations in central Canada and the eastern United States, where forests had been seriously damaged by short-term planning and timber exploitation. Conservation policies required longer-term planning than the 21-year timber leases encouraged, and Allco had already been tasked with replanting in some of the older clear-cuts. The value of the forest was increasingly seen in environmental and economic spinoffs, in addition to its board-feet. By the early 1930s, Nelson Lougheed, principal of now-defunct Allco, was provincial minister of public works. He lobbied the federal and provincial governments for the creation of a park on the disused timber lands north of Maple Ridge. The local Gazette voiced support for the plan, extolling the need to protect the last “stand of giant virgin forest” in the Lower Mainland – and the need to replace the logging industry with the economic benefits of tourism.

The old area of Timber Berth W was protected after 1933 within the confines of Garibaldi Provincial Park. Access remained only on foot or by horseback, though many local residents were regular visitors to the abandoned clear-cuts and many small lakes. The area would be accessed by public road only in 1958, from which point its popularity within the Lower Mainland blossomed. Increased use led to the administrative separation of Golden Ears Provincial Park from Garibaldi Park in 1967. Meanwhile in 1949, the western portions of Timber Berth W, north of the Silver Valley area, had become the private “research forest” of the University of British Columbia under the leadership of F. Malcolm Knapp, forester and professor. The university was one of the promoters of the science of forestry, and Knapp himself was known for his belief in restorative management of forest resources. Much of the forested land in the area is now 60- to 70-year old second-growth, composed mainly of western hemlock, red cedar, and douglas fir. In Whonnock, Ruskin, and Webster’s Corners, private logging continued using government licenses. Following the Depression, these operations were smaller than the railway logging outfits and used flatbed trucks to move single logs felled from the woods. Truck logging was an integral part of clearing areas in eastern Maple Ridge for small-lot agriculture and rural settlement.

Today, parks and protected areas pepper Maple Ridge’s forests, affording the community access and recreational opportunities. “Re-creation” is a good word to describe how we see the forest today. We might appreciate it because we value its beauty or believe the experience is wild, but the trees themselves will always contain another history: one that speaks to the spirit of early industry and the environment’s seizure and sale – the exchange of the forest for trees, and the trees for timber.

You can see artefacts relating to the logging industry in Maple Ridge at the Museum, where Timberland is on display.