WARNING: THIS POST CONTAINS NEWSPAPER ARTICLES WITH OFFENSIVE LANGUAGE AND OUTDATED CULTURAL REFERENCES.

The Early Years:

The first Japanese Canadian settlers arrive in Maple Ridge in 1907, mostly buying farmland and settling in as berry farmers. At the time, work could be or had the potential to be short for Japanese Canadian men, as most business in B.C. were owned by white setters, who could not always be counted on to hire non-white workers. Japanese Canadian settlers therefore were encouraged by their fellow issei (first generation Japanese Canadian settlers) to take their future into their own hands by buying land and farming.

Center – 1945. Displaced in wartime to the Fraser Canyon near Lillooet, the Tsuyuki family grew a crop of huge zucca melons for the candied peel trade (P03384)

Right – Japanese Canadian women and children picking strawberries at their farm in Whonnock in 1941 (P06675)

By 1927, 5,728 acres of British Columbia were farms owned by Japanese Canadian families, 2,378 of those acres were in Maple Ridge. One-third of the Japanese Canadian population lived in the district of Maple Ridge on 220 family owned farms. That was 30% of the population of Maple Ridge.

The first greenhouses in Maple Ridge were started by farmers like Tokutaro Tsuyuki and his wife Tori Hara. Despite the large and productive berry farms, the early Japanese Canadian settlers found it difficult to get their produce into the Canadian market, which often discriminated against non-white business partners. Out of a need to break into this market and sell their produce, the Haney Nokai was created. An agricultural collective co-op, the Nokai was a go between with the Japanese Canadian growers and white sellers. Eventually, the Nokai grew from an agricultural collective into a cultural institution.

There were culture clashes in those early years between Japanese Canadians and the non-Japanese majority (known in Japanese as the hakujin). Mostly small cultural differences, these clashes had the potential to become larger issues. With a desire to live comfortably and safe, the Japanese Canadian community turned to the Haney Nokai, to understand and address complaints from the hakujin. Some farmers and Maple Ridge residents openly accused Japanese Canadian farmers of taking jobs from white settlers, an argument, it seems, as old as time. The cultural clashes being mostly small, the Japanese Canadian community always ended up making the concessions and adapting to the cultural institutions of the hakujin farmers, including not working on Sundays.

Read more about the Haney Nokai here.

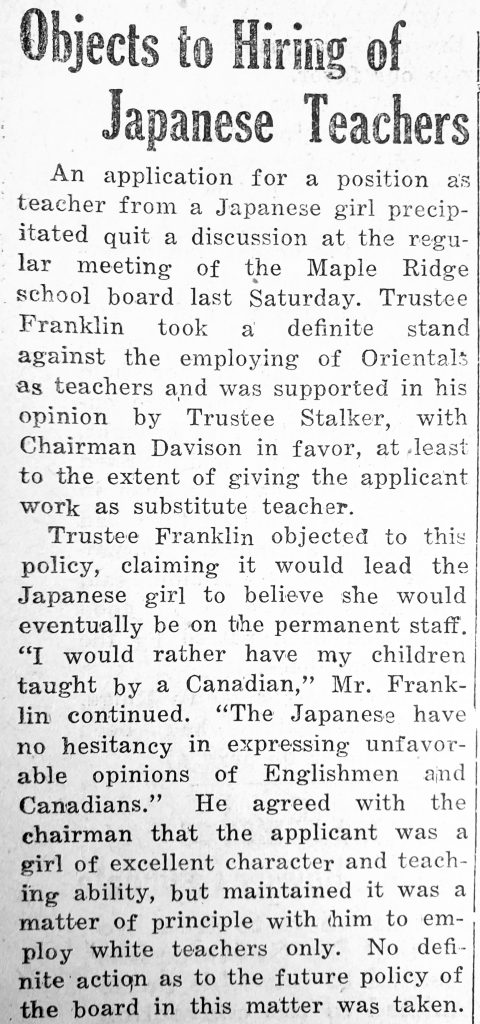

Articles in the local paper point to other anti-Asian forms of discrimination and resistance to cultural diversity. In particular, the school board was resistant to hiring Japanese Canadian teachers. While much of the local school population was made up of Japanese Canadian children who were born in Maple Ridge, only white teachers were hired.

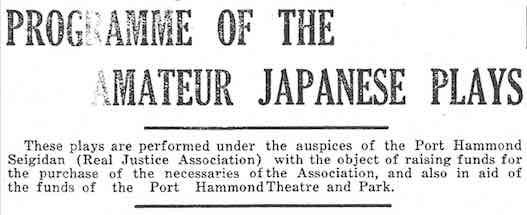

Community halls, schools, and temples were constructed in nearly every neighbourhood of Maple Ridge. The Hammond Nokai constructed a hall and were active in the Hammond community. In 1924, the Japanese Canadian community in Hammond put on a series of traditional Japanese plays for a fundraiser, sharing Japanese culture with the rest of the community. There were Japanese Canadian community halls and schools in Whonnock and Ruskin. In Haney, a Buddhist Temple was built at Dewdney and 216th, it would later become the Dutch Christian Reform Church, then a series of pubs. It is still standing today. On the corner of Dewdney and 232nd there stood the Haney Nokai hall, a Japanese language school, and a small building used for young boys practicing Judo.

By the 1940’s most of the Japanese Canadians citizens of Maple Ridge were the nisei (second generation of Japanese Canadians) and were born in Maple Ridge. These children of the first generation of the first Japanese Canadian settlers were brought up in two worlds. Going to school alongside the hakujin children, the nisei would also attend Japanese language schools and work in the fields of their parents farms. The cultural differences that separated the issei and the hakujin were less among the nisei, who grew up in both Canadian and Japanese cultures.

After 40 years of establishing themselves as a large part of the agricultural and cultural community, clearing land, starting businesses, building the first greenhouses in the district, and building temples, halls, and schools, World War Two began and things began to rapidly change. Internment was not immediate with the declaration of war. The fear based racism against Japanese Canadians in B.C. began with war measure acts limiting farmers purchasing power, instituting curfews, mandatory fingerprinting, telephone and driving ban, and eventually Japanese Canadian community halls and schools were closed. In 1941 Japanese Canadians were “asked” to voluntarily identify themselves in a census. Then by 1942 they were required to submit their identification for census and later that year the “evacuation” of Japanese Canadians began.

Internment:

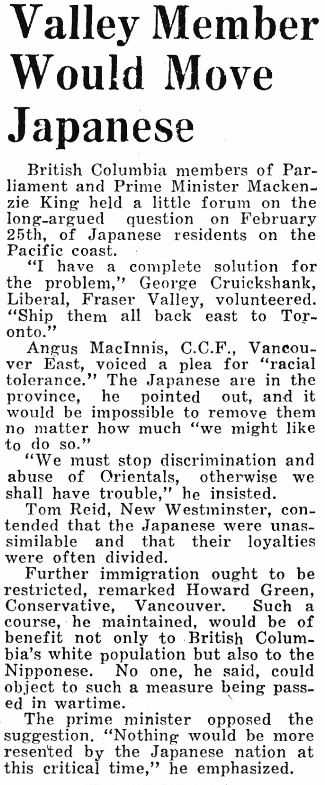

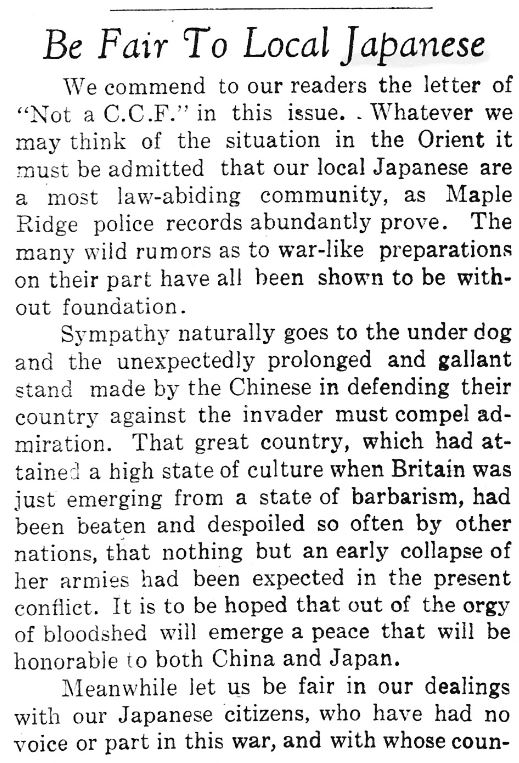

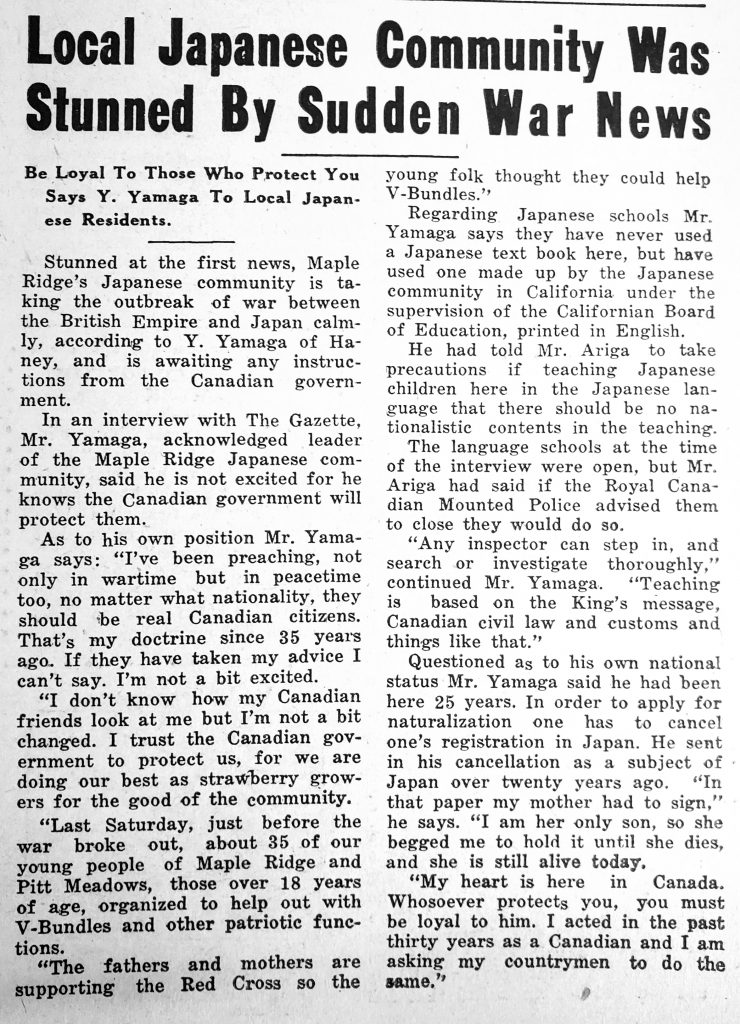

Internment was being debated in Canadian and British Columbia politics since the beginning of the war. There was support for the Japanese Canadian community by their neighbours in Maple Ridge, a letter to the editor shows support and an urge for civility. However, another article displays part of the political debate, from March 16, 1941, with the MP representing Fraser Valley (which included Maple Ridge at the time) arguing in favour of internment.

The Japanese Canadian community in Maple Ridge, most of whom had never even been to Japan, made it known in the local paper that they were shocked by the actions of Japan with regards to their war efforts, expressing their love and support for their fellow Canadians, and Canada’s fight in the war. In fact, there were men in the Haney Nokai who themselves fought for Canada in the First World War, including George Shoji.

In April 1942 all Japanese residents were given their orders to vacate their land and property and were moved to farms or internment camps far away from the coast. Their lands and property were turned over to the “Custodian for Enemy Alien Property” for “safekeeping” during the war. Not trusting this system, at least one Japanese Canadian family buried their valuables on their family farm. Others sought the help of their non-Japanese neighbours, who initally promised to keep their property safe for the duration. At the time there was much anti-Japanese sentiment at the national, provincial, and municipal level, but there were also those who stood up for their Japanese Canadian neighbours.

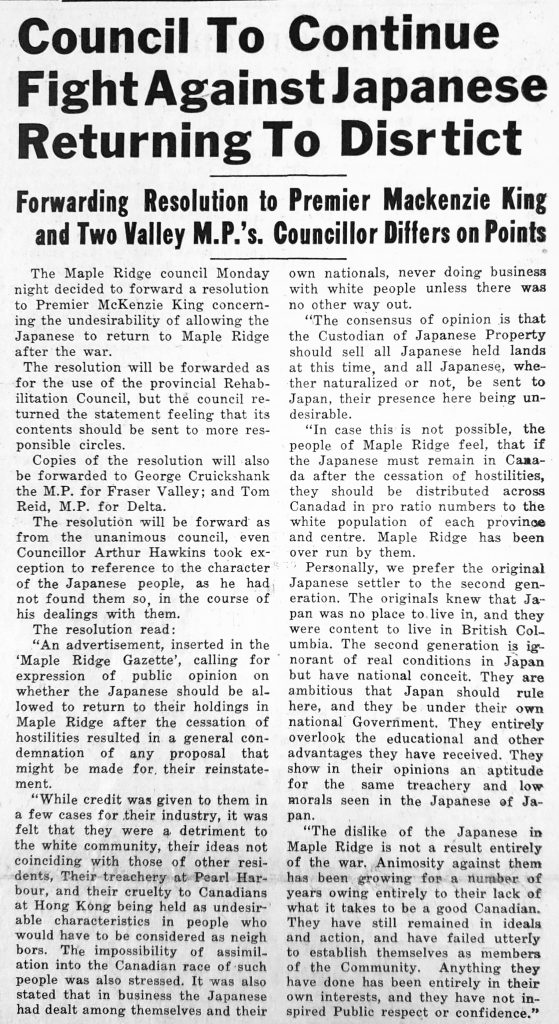

Internment and deportation was supported by the city council of Maple Ridge in 1942, with a unanimous vote being held that the Japanese citizens of the district should not only be interned, but not welcome back after internment, with their lands and holdings being sold and redistributed. This came after calls and a petition from community members calling for the Japanese Canadian owned lands to be redistributed. The city council notes (article below) that Japanese Canadians should not be welcomed back to Maple Ridge “The consensus of opinion is that the Custodian of Japanese Property should sell all Japanese held lands and at this time, all Japanese whether naturalized or not, be sent to Japan, their presence here being undesirable” further stating that “The dislike of the Japanese in Maple Ridge is not a result entirely of the war. Animosity against them has been growing for a number of years owing entirely to their lack of what it takes to be good Canadians… they have failed utterly to establish themselves as part of the community.” This vote would become reality, by 1949 all Japanese Canadian lands and assets were sold and of the 300 Japanese Canadian families from Maple Ridge who were interned, only 7 returned.

After the War

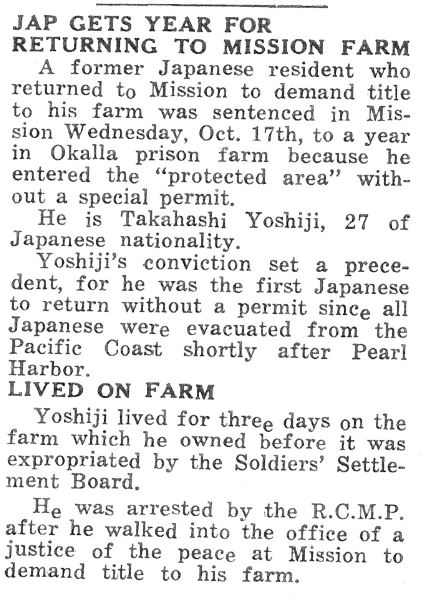

Through the end of the war and after, nearly all the lands, property, and goods confiscated by the Custodian of Enemy Alien Property were “disposed” of, with no compensation being given. Until 1949, Japanese Canadian citizens were required to have a permit to enter the restricted area near the coast, including Maple Ridge, or else risk imprisonment. A Japanese Canadian farmer from mission was arrested and imprisoned in 1945 for entering the office of the justice of the peace to lay claim to his land. The war had been over for two months, he got one year in prison.

The lasting effects of internment were felt for many years by the Japanese Canadian population, completely displaced by the fear and racism of the ruling majority. This policy of internment changed the landscape of Maple Ridge forever. Even today we can see buildings, parks and farms, originally built by the Japanese Canadian community that are no longer the Japanese schools, temples, or farms. Despite discrimination before internment, and the devastating effects of the evacuation, the Japanese Canadian community of Maple Ridge made a positive and long lasting effect on their neighbours, our history, and development. Those evacuated remember their childhoods growing up in Maple Ridge fondly. Today, the Haney Nokai are honored for their huge cultural contributions to the district, with a park in Haney.

Our records at the museum of the Japanese Canadian community can often be scarce, disjointed or simply missing. Because of internment, many of these families did not return or had their own family records and photos lost. We are always looking for documentation, photos, and/or stories of the early Japanese Canadian settlers to Maple Ridge to add to this part of our local history.

For more information on the Japanese Canadian Community in Maple Ridge history, see these posts for information on specific families, experiences, and artifacts in the museum collection.